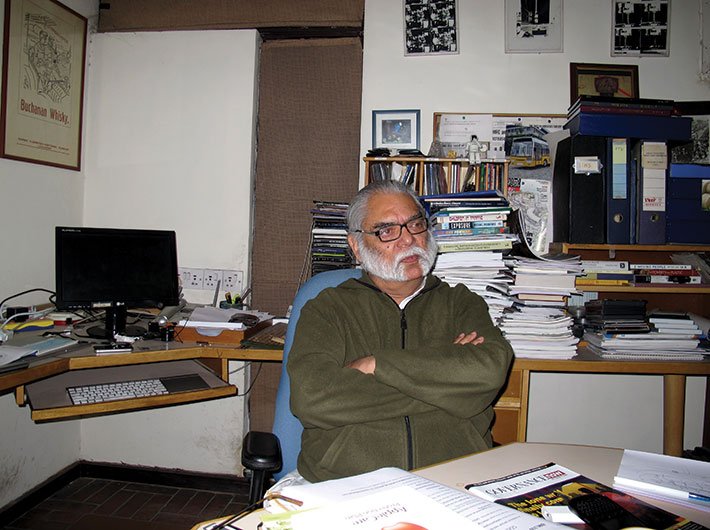

The emeritus professor at IIT-Delhi’s centre for biomedical engineering, Prof Dinesh Mohan was formerly the coordinator of transportation research and injury prevention programme. He tells Sopan Joshi about the state of knowledge on road safety and the politics of public transport:

How does India perform on road safety parameters?

If you consider deaths on the road per thousand persons, we are somewhere in the middle. South Africa, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Thailand do worse than India. There are rich countries that do badly. The death rate in the US is about the same as India.

The best road safety performance comes from Sweden, Japan, Norway, the UK and the Netherlands. China, on the other hand, may have numbers higher than us, because their numbers are not very reliable. Very few of us believe the numbers from China.

Not that we have very good numbers in India.

How do our cities rank?

Somewhere in the middle, again. There are cities with more deaths than our cities (but none in countries that do very well on road safety). My suspicion is Johannesburg in South Africa and Tehran in Iran do worse than our cities. Within India, Delhi is somewhere in the middle. Agra is much worse, Bengaluru and Chennai are worse off. In India, people in general don’t know how to look at numbers. It is a social comment. There is very little expertise in any field in our country.

Please give a few pointers on road safety.

Unfortunately, telling people what is correct has not done any good. That’s what our experience tells us. So I’d say people should force police and authorities to put speed breakers in their localities, anywhere and everywhere they walk, especially children. The number of people being hit even in residential areas is not small in India. If you go to a hospital and spend some time there, you will see several cases of people hit by motorcycles inside residential areas. These injuries are not minor. Don’t forget, the acclaimed scientist Obaid Siddiqi died in 2013 after being hit by a moped outside his house. The real problem is not the people; it is the experts in the field.

You have also been talking about roundabouts.

Take the example of Europe, which has had an epidemic of roundabouts for the past 20 years. Thousands upon thousands of traffic signals have been removed and replaced with roundabouts, because they reduce death rate by about 80 percent and air pollution by about 30 percent. In India, however, there is no civil engineer – not one – who knows how to design a modern roundabout. Not that it is difficult. It is possible to train people to do this within a year. Since it is not considered important, it is not done. Our engineers do not acquire the knowledge that they can easily get. Though some of us have been talking about roundabouts for 15-20 years, nobody has picked it up. The only caveat here is: I’d do a few experiments for a year or two first to see what changes we need to make in the modern roundabout design to suit high traffic of motorcycles and other vehicles.

Other ways to make roads safer?

Basically, anything that reduces speed inside the city, because our speeds are too high. New York City has just reduced its speed limits to about 40 kmph. But we still have newspapers like the Hindustan Times and The Times of India asking for an increase in the speed limit. It is almost compulsory to have speed-breakers every 80-200 metres on all roads near residential and shopping areas, schools. In IIT-Delhi, we used to have one accident of some kind every week on campus about 20 years ago. We tried everything, talking to the faculty, a campaign among the students, but nothing worked. So we built speed-breakers every 100 metres on every single road in the campus. Now we hardly have any accidents. We need different ways of controlling speed, if possible by design or by patrolling on the main road. You cannot have enough policemen for residential areas and minor roads. So there, you control speed by design. Make the road narrow, make turns sharp. We should not have smooth turns in the city, so that everyone has to slow down. Indian civil engineers still don’t know this so they still use designs from

60 years ago.

What are the design issues outside the city and inside?

All our highways have a raised median. That is not allowed by design in any civilised country in the world for the last 40 years. Because when you are going at a high speed and your tyre so much as touches that median by mistake, it disintegrates in a fraction of a second and the rim gets completely demolished. The car climbs on the median, launches into space, turns, and falls on its roof. It is the same case with our sidewalks. So we are the only country in the world where cars overturn inside the city because of the design. You cannot have anything raised that high along a high-speed road. Such design issues don’t get discussed because they are not sexy enough. Talk of the number of traffic violations gets attention, talk of more strict punishment and more education, etc.

How do we change the driving culture?

Policing. We have about the lowest presence of policemen doing their work on the roads. Even when they are there, they have not been trained to do what they should be doing. After union minister Gopinath Munde’s death in a road accident, suddenly we had police officers saying on TV shows that we need technology, we need cameras, hardware (when the problem is one of software, that is, the training). One man actually said that in foreign countries, you don’t see policemen on the road. It is exactly the opposite. In developed countries policemen drive around all the time, while there is very little patrolling on our roads.

Any other tips?

Motorcyclists keeping their headlights on all the time is a simple, easy solution to preventing serious injuries. Because you become more visible in the peripheral vision of drivers of big vehicles, especially in countries where you have bright sunlight. We have data from two such countries, Singapore and Malaysia, to show that you can reduce accident deaths by 15-20 percent. This is so easy to enforce: just ensure that the light comes on when you turn on the motorcycle. This was discussed in a conference that we had jointly organised in 1991, where a resolution was passed to this effect in the presence of the transport minister. Yet, every secretary who takes over has asked me for a note on this for the last 20 years. Still, nothing has happened. Another small change is to ensure that children always sit in the back seat, not the front seat. The dashboard is a hard surface, and a child can break his teeth or jaw even at the speed of 10 kmph. Secondly, don’t keep your child on your lap. If you hit something, first the child will hit something in the front, and then you will crush the child. Seatbelts are another essential.

Will changing the licencing system reduce lawlessness on the road?

No. Only enforcement will change it. It is very easy to get driving licenses in so many countries. You go to Kampala in Uganda; they behave better on the roads than here. This clamour for better driving training is what they were saying in the US in the 1940s. But look at Kuwait, where licensing is much stricter than in India. It has a much higher death rate than India. These things are difficult to get across to the general public.

How do you see the public vehicle-vs-private vehicle debate?

We may be the only country – or one of the very few – where you pay lifetime road tax on a vehicle. Most countries have a yearly tax. In addition, in some cities employers have to pay the transportation tax. Some cities have a pollution tax. We are the least taxed in terms of private vehicles. In terms of commercial vehicles, I don’t know about trucks, but buses are taxed very unfairly. If you consider per km travel, the bus passenger pays more tax than a private car. Compared to Metro, buses are taxed higher.

How does one address public transport?

Using public transport is a forced option for every human being who has a private mode. So, it has to be enforced. As a society we need to agree to control and regulate car use for reducing congestion, road deaths and pollution. No matter what you do, in the next 30 years no city will provide more than 10 percent of the total trips by the Metro. At present, Delhi Metro carries only 5 percent of the total trips. When you consider all motorised trips, Metro accounts for about 10-15 percent only. Delhi Metro costs '35,000 per passenger per year. In a country where health and education do not get enough funding, should we invest so much in it? Walking and cycling account for 40 percent in Delhi (in Mumbai it is 45-50 percent). The concept of the Metro is 150 years old, when there was no option for mass transit. Buses became viable only after World War II, when roads became better, pneumatic tyres became available and the diesel engine became sophisticated. Besides, Indian cities do not have the kind of city centres European cities have. Typically, trips in Indian cities are over short distances. Which is why our public transport has to focus on surface transport – a combination of buses, taxis, auto-rickshaws, etc.

How do you view Delhi’s BRT experiment?

The idea of the BRT began in India before the BRT in Bogota in Colombia. It is not that we saw something, got excited and wanted to copy it in Delhi. We did a study and gave a report to the government in 1996 that suggested the BRT. The media picked it up and the then transport minister of Delhi, Rajendra Gupta, got interested and commissioned a study. Then the Congress government came in, and transport minister Ajay Maken caught on to the BRT idea immediately. He organised a conference in Delhi. There, the chief minister announced implementation of the BRT. A government committee recommended five BRT corridors. The selection of the first corridor was an administrative one – the bureaucrats wanted a route that involved the fewest number of administrative authorities. Theoretically, there is no difference between trams (which are 120 years old) and a BRT corridor. Delhi is the only society I know of among about 400 cities where a well-designed and implemented BRT was subjected to such a negative public discussion. We told the government several times to have an advertisement campaign, but the government did not back up its effort with a communications campaign so that citizens would know why the BRT was good for the city. There was no effort to build wider political support for it.