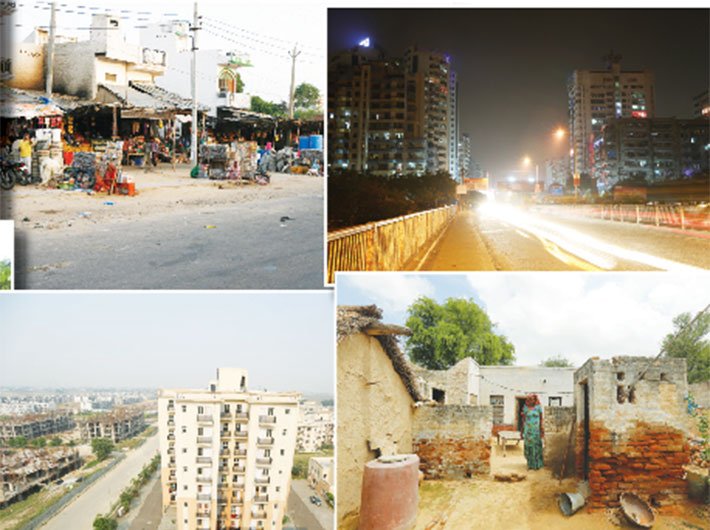

The stillborn promise of housing as a safe roof over everyone’s head is the result of a severe lack of imagination that can directly be traced back to systems thinking

In the final analysis almost all of politics and most of economics are connected to three critical human needs: food, clothing and shelter. In India we know it quite intimately having seeped deep into our popular culture as roti, kapda and makaan. Of course, in India as in several other countries, the three human needs are also liberally interspersed with all sorts of cultural norms, religious rules and social attitudes. These largely unsaid and usually invisible markers transform what otherwise could have been simple commodities into symbols of cultural identity and ideological positions. Such markers serve as context contributing to the larger cultural ecosystem. Equally, they are also derived from a larger national and cultural backdrop. Two illustrations about food and clothing should bring out the ideological and cultural spikes in a pointed manner.

A universal public distribution system and targeted food stamps is about first order principles and worldviews with food only as a second order context. Universal public distribution system is deeply rooted to the core value that everyone should have access to food to keep body and soul together and that responsibility solely and directly rests with the state and not with the market. Various permutations and combinations of food stamps are anchored to the value that access to food cannot be universal and that it needs to be modulated through access filters and mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion that have to be primarily located within the market ecosystem.

Similarly, jeans and skirts and salwar kameez and sarees are in the Indian context often about patriarchy and power dynamics than about the basic human need to protect against elements and the weather. So, when principals of colleges issue circulars banning girls from wearing jeans and skirts citing tradition and culture and strongly suggesting a shift to a saree or a salwar kameez, it’s a specific worldview depicting both a mindset and tightly coded hierarchy of power and control. In response if the girls of these colleges defiantly wear jeans and skirts as a response, it’s again a worldview that depicts a different mindset informed by resistance to being controlled and being told what to do. In both instances, clothing is a cultural and ideological weapon, removed substantially from its first order human conception as a means of protection from weather and its elements.

Why we need to understand food and clothing to unpack shelter

To the scientific eye, as opposed to an ethnographically tuned eye, food, clothing and shelter are three separate human needs, more biological than cultural or sociological. They are mainly conceived as commodities whose demand and supply can be controlled by technology, retail management and price points. Culture is but a minor additive in the scientific scheme of things. Yet the three are not only heavily moulded by culture and society, as the two examples above clearly show, but are also interconnected with each other as cultural products emerging from particular worldviews. In exploring and understanding the nature and character of food and clothing, two clear contexts are established. First, food and clothing are a constant backdrop – both as a lens and deeply personal gaze – of everyone’s daily life in urban areas. Second, the extraordinary transformative power of food and clothing to become anything but food and clothing is a necessary condition for planting definite signposts in order to ground how the concept and practice of shelter has panned out in India and the world in general.

In some ways, shelter is like food and clothing sieved as it is through similar cultural and ideological filters. In that respect, one can literally trace back the conceptual moorings of ‘public housing’ to specific ideological and cultural standpoints emerging from a worldview of housing for all, as one can unpack ‘affordable housing’ to a complex belief system that market mechanisms have an innate ability to evolve a super flexible frameworks that can accommodate everyone irrespective of their access to social and financial capital. Yet shelter is also fundamentally different from food and clothing in terms of complexity and layers. The difference is not because there is less of a sociocultural context, ideological vantage points or worldviews surrounding shelter, but the difference is that all social complexities surprisingly converge on one common manifestation of shelter: a house.

Some explanation is required and we will have to turn again to food and clothing, but more as nodes to compare why shelter has not acquired the same degree of cultural, political and social complexity as food and clothing. Both food and clothing have reached the pinnacle of human derivation.

The highest possible derivative for any commodity – anything that you can touch and feel in a material and physical manner – is for it to be imagined and positioned as sacred and divine. In being transformed as a sacred and divine object, that particular commodity escapes the ‘human orbit’. An offering to a god or an otherworldly entity is no longer within the realm of human reason and rationality, and that in itself is an extremely powerful position to be in. So, an offering of a nine-course meal to a god or a godly figure in a temple keeps that particular meal away from the human realm, at least temporarily, till it’s blessed by the god or the figure. Just as freshly washed, clean and unstitched clothes needs to be worn in order to enter the sanctum sanctorum of several temples. In both cases, the social and cultural derivatives of food and clothing – both material commodities –permeate the realm of a non-material norm.

Notions of shelter are essentially a modern imagination born out of systems thinking and its follow on logic and rationality of size and scale. For all its urban complexities, shelter’s highest human derivative is relatively simple (relative to food and clothing) and firmly in the material domain. In a sense, then, especially in comparison to food and clothing, the different manifestations of shelter largely come down to some form of housing, some form of access to it with both being firmly placed within certain parameters of price and affordability. Everything else is, in more ways than one, bells and whistles. Let’s give this seeming abstraction called shelter a form and shape to help us understand its essential manifestation.

The typical urban dream is to own a house. The size and scale of the dream is limited only by two factors: access to finance (as in cold hard cash) and access to social capital (as in status, network and the right circles). When someone has both, and in good measure, the house has all the bells and whistles that one can think of – swimming pools, sensors, terrace garden, climate control and of course the all-important right address, which is often a matter of social capital rather than just pure financial muscle. When someone has predominant financial muscle, it’s likely that one may end with all the bells and whistles but may not land up with the right address. And when someone has more of social capital than monetary one, there are other kinds of privileges that are available that can range from club memberships to off-market rates and deals.

Yet, the highest manifestation of the notion and imagination of shelter is a house. Unlike contestations about what actually constitutes food and clothing – organic or processed is one illustration – no modern cultural context, political philosophy, social structure or a governance system – democratic or autocratic – as a matter of first principle denies that shelter’s most direct manifestation is a house. The simplicity that was mentioned earlier comes from the fact that all modern worldviews translate shelter as housing. Of course, there are several finer positions that argue with enough justification that transforming a house into a home is as much a matter of personalising a space as it is about individual rights, private property, privacy and a clear distinction between the outside world and the personal world. There are also equally strong arguments that trace their lineage to some of the traditional worldviews, especially Asian ones. Such argument posit with equal justification that homes in the modern sense are not homes of the yore, which put communities and extended families at the centre. In such imaginations, modern notions of public and private space were not the primary defining factors of what is home and what is not. Despite these finer nuances, shelter is first and foremost seen as a house.

House, housing and the limitations of systems thinking

Let’s again get back to food and clothing to understand why systems thinking has not really turned out to be the ‘one size fits all’ solution to all daily issues of urban life equally, especially to the issue of shelter and its solutions of housing. Food has a certain context, which I have explained in detail in my previous column (Please see ‘Feeding yourself in the city of future: Food as urban sovereignty’ in Governance Now issue dated September 30, 2017). The long and short of my argument is that food has never been considered urban, having been confined as an activity of the rural areas. Behind that notion is the urban-rural distinction powered by systems thinking. In short, rural areas were seen as one big farm. Green revolution, in India for instance, is a good illustration.

Clothing’s most direct manifestation in urban areas is fashion and trends. While, unlike food, it has become an integral part of a modern city’s brand identity, the production of clothes in itself, however, has always been considered as an activity that needs to be concentrated and confined to peri-urban areas or large special economic zones just outside the city. One can pick any typical large clothing brand and its factories outside Bengaluru or Mumbai as an example. In more ways than one, food and clothing have moulded their production, distribution and consumption mechanisms to systems thinking in remarkably similar ways. This has, of course, led to scale and size as one would conventionally define it in terms of large food and clothing factories, last mile market-based distribution mechanisms and an increasing standardisation of ‘choices and offerings’. A Big Bazaar in India or a Walmart in several parts of the world is an apt representation of systems thinking’s impact on both food and clothing: neatly packaged, fairly standardised, industrial and available on a mass scale.

There is some justification in crediting systems thinking for the availability, relatively easy access and wide variety of price points as far as food and clothing in urban areas is concerned. Of course, there are other issues emerging from the very same systems thinking ranging from unreasonably high levels of chemicals and sugar in processed food to food deserts that has led to global diabetes and coronary epidemics. The same framework of systems thinking has failed quite miserably in creating size and scale as far as house and housing is concerned. The only exceptions have been massive public housing projects spearheaded by state and state-led institutions that have moved beyond the logic and rationality of systems thinking and the business model approach. Singapore’s public housing model is an excellent example of a state-led public housing model where housing was seen as necessary part of human development, leading to different approaches to calculating returns on capital investment, setting up non-financial incentives and community-based regulation and policy frameworks.

However, the overall failure of systems thinking stems from three factors. First, housing has never been commoditised to the same extent as food and clothing. In simple terms, one cannot go to a mall and buy a house.

Second, urban notions of shelter and its manifestations of a house and housing cannot really be constituted as a rural or a peri-urban activity. Even in cases where housing is suburbanised or peri-urbanised, its raison d’être almost rests exclusively on its ability to access the urban centres in the least possible time with the least possible cost. In simple terms, the associated infrastructure of mobility and access becomes as important as housing itself making the entire system complicated. Systems thinking results in scale and size when there are only a few moving pieces that allow simple models to be quickly and easily replicated. It’s precisely why McDonalds, Big Bazaar and H&M with a few moving pieces have scale and size, while public housing with its myriad moving pieces doesn’t.

Third, shelter in the way it has been unpacked as house and housing has resulted in a logical extension that has turned a house into a property and by default an investment for life. In simple terms, a house gets intersected by a logic map of security, returns, financing, loans, interest rates, future planning and legacy, which is not the case with food and clothing. In short, ‘systems thinking’ infuses every house with a value proposition that turns it into probably the most prized possession for the individual and family, a sort of a music score that starts informing everything from access to financial capital to risk assessment. In short, unlike food or clothing, a house is not seen as a disposable commodity with a short shelf life but as something that will make or define your life.

Quantum urbanism: Transforming shelter into a renewable and temporary resource

There are three questions that emerge from this failure of systems thinking. The answers to these questions are potentially emerging from the domain of quantum urbanism and its radically different pathways. The first question: Is shelter that complicated that you need large real estate companies, complicated policies and regulations, countless permissions, complex bureaucratic oversight and a construction technology that for all practical purposes hasn’t changed much in the last 150 years?

It’s a surprise for many to learn that construction technology is akin to internal combustion engine. The fundamental principles of both haven’t changed in over a century. There have been substantial improvements in both, as one can clearly see in cleaner hybrid engines, safer cars and stronger buildings, but the basic architecture and methods have remained the same. In essence, the construction industry still ends up taking anywhere between six months to a couple of years to execute any project of credible scale and size. The industry, and the various sectors that are part of its forward and backward linkages, still follows a pattern of working that hasn’t really been revisited in a substantial manner in over a 100 years.

Several groups of architects, designers, urbanists, anthropologists as also civil society organisations, neighbourhood associations, communities, groups and individuals are asking the same question in their own different ways. They are exploring and to their surprise, and to the surprise of many others, are finding solutions, technologies and methods that are already available that drastically change the architecture and methods of construction. Two groups, one in Finland and one in Coonoor in Tamil Nadu, are already working with renewable resources – in this case wood – integrating local communities and their age-old knowledge systems with absolutely new compacting technologies that makes wood substantially stronger, as strong as steel in some critical parameters, while making it weatherproof, termite-proof and even fire-retardant. These two groups, using modular architecture and prefabricated technologies, are putting up houses, some large enough for extended families, in as little as 15 days and at one-tenth the price of a conventionally constructed house. Both groups are so confident about the robustness and safety of the houses that they are giving each house a 25-year guarantee. There are similar groups using other locally available materials ranging from mud to rocks like granite, basalt and limestone.

The second question has two parts, more like two sides of the same coin: Is a house really an investment? Why can’t it be commoditised enough for people to stop assigning it a special value and treat it in a similar manner as food and clothing? There are groups of people – an expanding breed – who are saying a resounding no to the first part and an equally resounding yes to the second part of the question. Needless to say, a majority of this group is composed of young single urban professionals, both men and women, who are consciously deciding not to root themselves to any place or large physical assets. One young management professional who had risen up the ranks and was a colleague at a large company that I worked with previously – and I will not name either – is a good representative of this group. “I want to travel the world and be at different places,” he said. “The day and age of a job, career, conventional marriage, children, all of that is over. Why should I spend my money on a house? It just ties me down.”

He has invested his money buying a clean ‘hybrid SUV’ and acquiring what he calls a ‘modern, state-of-art tent’ from South Africa and a portable chemical toilet and bathroom from Germany. He spends six months travelling and six months working. He calls his tent and portable toilet his home, and stays in hostels and small Airbnb rooms when he is working in a city. His closing line is a clear indication of emerging quantum change in mindset. “My tent is like a good pair of jeans. It’s comfortable and I know I will use it well. But after three or four years, I will change it. I am sure I will get bored of it. Maybe I will get a foldable home,” he said. Just in case you are wondering, foldable homes are just round the corner. Just as one can go to a furniture store and get everything in knocked down condition and put it all together, in a couple of years one can actually go to a housing mart and buy your own house and install it a day or two.

The third question: In this emerging quantum world, how do you create scale and size for housing? At its simplest form quantum urbanism operates at the hyperlocal level and acquires greatest traction with small groups and communities. That’s the nature of quantum urbanism. Within that context, scale and size seem like a misnomer. But it’s here that the quantum principle of multiple states actually comes to bear. In the Swedish island of Gotland is Klintehamn, a small place of just 1,350 people. There is a little bit of a radical thought process being executed here. The place became the hub for a whole host of migrants who were fleeing the violence and conflict in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. The community welcomed them with open arms having opened its arms before to Iranians who felt the Islamic revolution of 1979 and the Afghans who fled the Soviet occupation of their country in 1980 (remember this is Sweden where liberal politics and inclusiveness is still quite deep-rooted). Of course, there was the practical issue of ‘housing them’ with dignity and respect and in a responsible and accountable manner.

The community got together and discussed at length. At the end of it all they decided to junk traditional notions of what is public space and what is private. While a lot of the migrant families were accommodated by the locals in their homes, some of the large public spaces – community halls, gymnasiums, schools, libraries – were thrown up to architects, designers, urbanists, companies specialising in new-age materials with a specific challenge: design them in such a way that they are homes as well as schools, community halls, gymnasiums and libraries. The solutions that have come up and have been implemented are radical in the way they have redefined space and shelter, while keeping key elements of work and home, private and public, individual and collective distinct. A lot of thought innovation has come from design thinking and platform thinking. Practically, the innovation has come from the use of lightweight, new-age and extremely strong foldable materials. Such is the flexibility of the design of these spaces that it keeps transforming into different places – a school during the day, home during the evening and night, a weekend gathering place during weekends. Its success has prompted policymakers to seriously start considering how to use empty offices spaces in the entire region during non-working hours in a more productive and efficient manner.

It’s in the exploring, understanding, adopting and adapting to the emerging quantumness of our daily lives and realities that we are going to start finding solutions to our increasingly complex and complicated issues of sustainability and resilience. It’s also in accepting the realities of quantum urbanism that the stillborn promise of systems thinking can finally be laid to rest and new ways of thinking can be birthed.

Next: Moving people, not cars: The future of mobility and urban life

Swaminathan is visiting research fellow at Uppsala University Sweden where is part of the project ‘Future Urbanisms’. He is also research director of the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy (CSIP), Ashoka University.