Tribal regions seem to have fallen off the country’s map. What matters for New Delhi, as this book vividly tells us, is the corporate greed for its rich mineral wealth

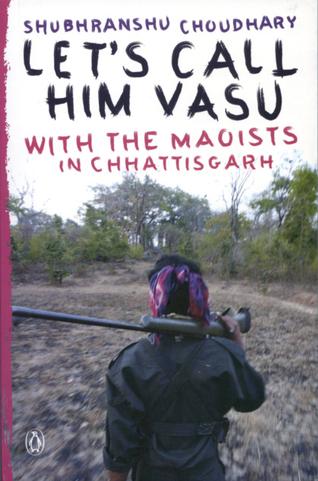

Let’s Call Him Vasu: With the Maoists in Chhattisgarh

By Shubhranshu Choudhary

Penguin, Rs 350

Two disclaimers would be required to foreground a review of this racy read.

First, absolute objectivity is a misnomer. Journalism, like any other cultural craft, is a form of fiction that merely hinges on facts. Stories are built block by block with facts, figures, backgrounders, quotes and juxtapositions, and polished with skills and workmanship. Journalists choose some building blocks over certain others. The second disclaimer is that one man’s terrorist will always be another man’s freedom fighter. The usage depends on which side of the fence the observer is located.

Choudhary, who trudged through dense forests in the heart of India’s ‘red corridor’ over many years, has tried to maintain a balance by borrowing perspectives from all sides: cops, ‘dadas,’ Gandhians, academics and politicians. He also happens to be a local boy from Chhattisgarh. He assails the Indian state for its betrayal of the tribal cause, admires armed cadres for their dedication but cannot find traction in the Maoists’ ideology of a curiously simplified version of Marxism. There, perhaps, lies the book’s biggest paradox: that the hardliners find it mildly sympathetic to the Maoists and the movement’s sympathisers characterise it as dodgy and irresponsible. And, for that reason alone this journalistic account is eminently readable.

Choudhary’s book is not primarily about the tribals despite his deep concern for them. It is an account of his tortuous journeys through the forests and the narratives of his meetings with all types of Maoists, ideologues, foot soldiers and top commanders. One is struck by the ease with which the world’s biggest democracy deals with what it calls the nation’s biggest internal security threat, by routinely burning houses, razing hamlets, spraying bullets on desperately poor people, and by systematically using rape and torture as instruments of dominance. By default, the gambit works as the Maoists’ raison d’être and their rationale for recruitments. Choudhary reinforces that in its quest for a high GDP growth rate, the state works for the mining companies and their corporate interests, and at enormous cost to tribal lives, livelihoods, and cultural mores.

Call it poor governance, skewed priorities or democratic deficit, the tribal India seems to have fallen off the country’s map. What matters for New Delhi, as the book vividly reminds us, is the corporate India’s interest in its rich mineral wealth and, of course, the Maoists’ presence. The villagers are seldom asked for their views or preferences before their homes and fields are given away for mines and factories. There is no question of treating them as stakeholders. It is not for nothing that almost all such areas are Maoists' strongholds. The author visited one such area in Abujhmad forest where 52 villages were ordered to relocate to make way for Indravati national park and 50 more for the Pamed wildlife sanctuary.

Choudhary also shows why the Maoists are opposed to roads, bridges, and school buildings, which they believe are being fortified for the CRPF, even though the state is leading a ‘development offensive’. Never mind if such development comes through the hopelessly inept and crooked troika of DFO, SP and collector. Even though some of this has been known for a while, the first-person account offers a panoramic view of the forgotten India. One also comes to know that Chhattisgarh’s success story of public distribution system (PDS) fails in forested areas due to high travel and opportunity costs involved. The book is not profoundly political and avoids any meaningful discussions on constitutional provisions like PESA, Forest Rights Act or the Fifth Schedule in tribal zones.

Parts of the narrative where top Maoists share details of their party organisation, military devices or war strategies with the author come across as rather naïve. However, one gets an idea of how easily young lives are ‘factored’ when senior Maoist leaders mount their retaliations. The book is not without unique insights about teenaged fighters, particularly young tribal girls, who form the backbone of the armed movement. Women make up almost 60 percent of the ground forces and even the best informed ones have not been to a proper city or travelled in a train. Despite increasing numbers, the tribals end up only as the movement’s foot soldiers almost never rising to become leaders or commanders. Their idea of the enemy state is confined to their impressions of the forest guards or the lower rungs of the police they grow up hating.

The book offers spine-chilling account of the state-sponsored vigilante apparatus called the ‘salwa judum’ which is mercifully disbanded after the supreme court’s intervention. For years, the centrally planned operation made a mockery of India’s democracy just to intimidate into submission, and kill and maim, anyone who disagreed with the state’s idea of development. The book chronicles some of its activities from the very beginning, including the use of the Naga battalions, and quotes victims and perpetrators alike. One is surprised to see different members of tribal families joining the opposite sides. A young man from the family of salwa judum’s best-known political face, Mahendra Karma, is a Maoist foot soldier looking to ‘finish’ the ‘man eater’ who happens to be his grandfather. Salwa judum sacked and looted his village several times and one of the 110 houses once burnt down was of this young man’s family.

Choudhury’s book is currently in news for outraging human rights activists, sundry supporters of the tribal cause, and diehard Maoist sympathisers. The big charge is that while being laudatory about some controversial cops, he has unnecessarily weakened social activist and paediatrician Dr Binayak Sen’s case in the court of law. He has ‘found’ in his casual conversations with known and unnamed Maoists that ‘Binayak-da’ was acting as a courier on their behalf, though one fails to understand why he couldn’t have kept this uncorroborated nugget of information out. Gandhian activist Himanshu Kumar, whose ashram was blatantly bulldozed by the police in Dantewada, and whose valuable support is acknowledged in the book, is also upset because he thinks it exonerates some the most vicious and corrupt officers, though Choudhay has vehemently countered the charge.

A reader will find out very easily why the legendary war correspondent Philip Knightly described the truth as the first casualty during conflicts. The home ministry goes out of the way to describe the situation in the ‘red corridor’ as an ‘all-out war’ because it can brand all its opponents as enemies of India. For it can also justify its rampant human rights violations as a ‘painful’ necessity. The Maoists, in turn, derive their moral high ground mainly from the police atrocities. Choudhary’s book also comes as a rude reminder of how little the rest of India knows about the ground realities there. The media in Chhattisgarh comes across as not just insensitive but truly compromised. A journalist of the local paper Hindsatt wrote about the cops burning down a village and was promptly ‘advised’ to retract his report by the local police chief. Soon after his refusal, he lost his job and his brother was jailed for being a ‘Naxalite’ and his house razed. Choudhary shows at many places how local journalists concocted stories or reported only the police version of events. One can’t expect better with the media houses either joining, or closely aligning themselves with, mining businesses.

The book review first appeared in the March 1-15 issue of Governance Now.