Censorship in India has of late become too depressingly common to be surprising. The latest victim is an award-winning documentary film, No Fire Zone: The Killing Fields of Sri Lanka, a portrayal of the last few months of the violent civil war in Sri Lanka. Last week, the Central Board of Film Certification declared it would not grant the film a certificate to allow it to be shown in Indian theatres. The Board decided that the visuals are of a “disturbing nature and not fit for public exhibition”. Also, of course, that the public screening may strain friendly relations between the two neighbouring countries.

But director Callum Macrae, even though hurt, was quick to reciprocate: on February 23, he put the entire 93-minute documentary on the internet, and made an announcement regarding the same. Which means anyone, anywhere, with an access to internet, can watch No Fire Zone—for free. The censorship was, for all practical purposes, rendered irrelevant.

Is anyone terribly surprised?

***

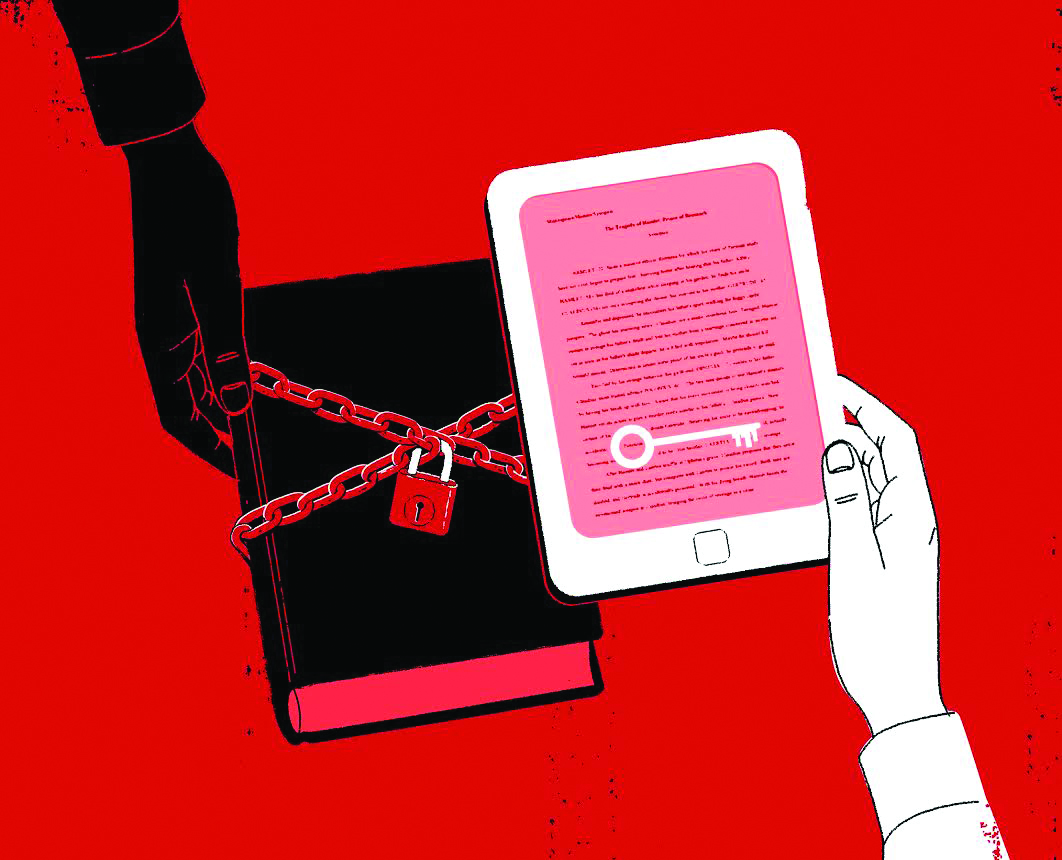

Even though the way censorship plays out varies with the medium, books have become the archetypal example of censorship. It could be a small group of individuals claiming to represent (often with no great legitimacy) hurt on behalf of a certain community: early February saw Wendy Doniger’s critically-acclaimed The Hindus: An Alternative History meet this fate. It could be an individual who finds his or her reputation at stake: in January ex-aviation minister Praful Patel successfully ensured that the hard copy of The Descent of Air India, written by former Air India executive director Jitender Bhargava, didn’t reach the potential readers. The exact legal clause varied but, to use the popular parlance, both the books got “banned”.

Prominent people voiced free-speech concerns: against publishers (Penguin India and Bloomsbury India respectively) for chickening out for a compromise; against the state, too, for the state has been an active enforcer of censorship—often for no reason other than petty political gains. All of this opposition was good, a healthy sign of a vibrant civil society.

Less attention was paid to a simpler question, though: is it really possible to censor a book, or a film—or any other content-driven product, for that matter—in 2014? The answer, though it may not register immediately, is: no. Not forever, in any case.

***

In a digital age, the disruption of ideas and institutions is no longer a bug, but rather a feature. And it works both ways.

Piracy on the web has world over robbed the music industry—and to a lesser extent other content product-providers like films and publishing—of massive revenues. Prohibition through legislation, even at its best, has not been able to offset the damage. Between 2003 and 2008, for example, the Record Industry Association of America filed, settled or threatened lawsuits against at least 30,000 individuals. And yet, the practice of file-sharing during the five-year period continued to grow there.

On the other hand, the internet has allowed the content-driven goods and services to transcend the traditional modes of information sharing with ever-updating, more user-friendly, and easily accessible, modes. And it is this universal democratization of information that renders very many censorships of present-day irrelevant, even counterproductive: anyone who wants to read either of the mentioned books has been able to find one: the e-book of The Hindus can be easily downloaded from one of the many blogs (even from Facebook and Twitter links); Bhargava has himself promised to release the e-book in the next few weeks.

Arindam Chaudhuri’s name deserves special mention here. Two years ago when Siddharth Deb’s book The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of the New India carried a profile of Chaudhuri, the ponytailed IIPM boss didn’t just file a suit against Deb, publisher Penguin India, and The Caravan magazine that carried an excerpt, he went on sue even Google India whose cache contained the relevant chapter. Unfortunately, neither of these methods helped much: everyone who wanted to read Chaudhuri’s profile in Deb’s book has been able to find a copy on the web (in fact, some pages can be read on Amazon’s websites, too).

Censoring a book or a film could have its benefits: political, religious, diplomatic, financial, and others. But in 2014 only the people least in tune with technological changes would censor content-driven goods and services thinking no one would find an alternate access. Nothing can stop, as the political economist Joseph Schumpeter once said, the “perennial gale of creative destruction”.

Citizens committed to enforcing censors have a rather difficult task at hand: update yourself with digital media; or the posterity would have more reasons to be sympathetic to you than to writers and filmmakers.

(This article appeared in March 1-15, 2014 issue of the magazine.)