In his book, Sitapati focuses on PV Narasimha Rao who unleashed historic transformation despite a minority regime

Vinay Sitapati, who teaches at Ashoka University and is finishing his Ph.D. in politics from Princeton, has written the book of the season, Half-Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Changed India (Penguin), bringing focus finally on that man with the famous pout who unleashed historic transformation despite heading a minority regime and battling internal and external opposition (and without help of social media). In an interview with Jasleen Kaur, Sitapati talks about the original reformer.

Vinay Sitapati, who teaches at Ashoka University and is finishing his Ph.D. in politics from Princeton, has written the book of the season, Half-Lion: How P.V. Narasimha Rao Changed India (Penguin), bringing focus finally on that man with the famous pout who unleashed historic transformation despite heading a minority regime and battling internal and external opposition (and without help of social media). In an interview with Jasleen Kaur, Sitapati talks about the original reformer.

History is not kind to all great men. Is this the case with PV Narasimha Rao too?

There is a very specific reason history has not been kind to Rao. Deng Xiaoping’s communist party continues to respect him, which is why today’s China venerates Deng. On the other hand, Rao’s own party has abandoned him. The Congress party has made a conscious effort to wipe out Rao from both its history as well as India’s history. Many charges have been made against Rao – most seriously of complicity in the demolition of Babri masjid. Even though, as my book points out, there is no evidence for this, the allegations have not been contested because there is no constituency which is pro-Rao. Historians also don’t like focussing on ‘great men’; they prefer to see historical changes as fuelled by structural forces rather than people. For many academics, the times were such in the 1991 that any other PM would have also presided over those changes. I don’t think this is accurate. The evidence is clear that but for Rao, India would be a different country today.

Narasimha Rao is often called an accidental prime minister, who had virtually taken political sanyas before he took up the top position. Yet, it was the most critical juncture for India, both economically and politically. How did he look at the task ahead on June 21, 1991?

Two days before he became PM, on June 19, 1991, Rao realised for the first time the scale of the economic crisis. He was an economic protectionist until then, and it is remarkable that he changed his mind into becoming a liberaliser in just a few hours. My book documents this transition in detail. When he became PM, he knew of the economic challenges ahead, and what needed to be done. He also realised that India was going through several other crises at the time. Since India’s global ally, the Soviet Union, was in slow collapse, India’s foreign policy needed to change. He also knew of the problems of insurgency in Assam, Kashmir, and Punjab. And he knew that India’s welfare schemes needed to be improved. When he became PM, he had no illusions of the challenges ahead.

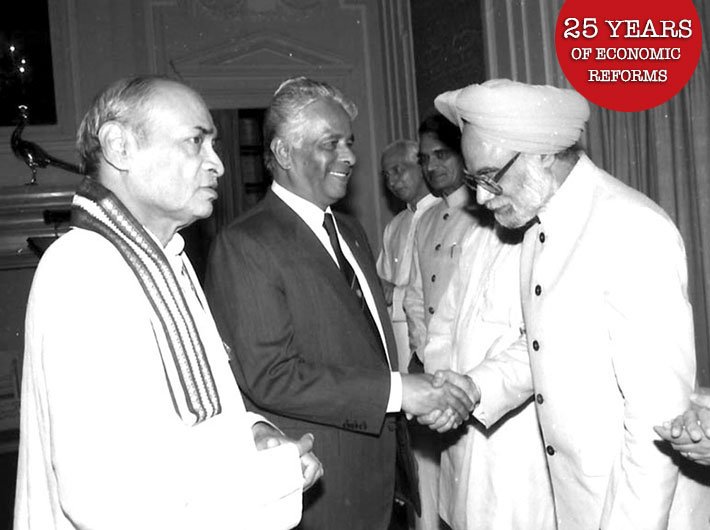

Many give the credit for reforms to Dr Manmohan Singh, who apparently was not Narasimha Rao’s first choice for FM. How were the personal equations between Rao and Singh before and after 1991?

Liberalisation was fundamentally a political decision, not an economic one. The economic blueprints for liberalisation were available to four PMs before Rao. But they lacked the political ability to deal with opponents. So there is no question that the 1991 liberalisation story is a political one and Rao is the hero. But Manmohan Singh played a very important role for Rao. They got along very well. Though Rao trusted very few people, he respected Manmohan Singh’s expertise. Since Manmohan Singh had a credible Western reputation, he was able to deal with the IMF, etc. very well in the early months of the reforms. More importantly, Manmohan Singh was a scrupulously honest technocrat who could deflect blame from Rao. Liberalisation was politically unpopular, especially with the Congress, and Manmohan acted as a shield for Rao, preventing attacks on him.

How did Narasimha Rao manage political opposition to the reforms, from both within the party and from the BJP whose agenda he was arguably hijacking?

I wouldn’t say he was hijacking the BJP’s agenda in 1991. As I say in the book, the ideas behind liberalisation were available since the early 1980s. What was needed was for a political leader to combat opponents to reforms. While the BJP’s trader base was for domestic liberalisation (de-licensing), they had problems with foreign competition. Also, even though the BJP was more sympathetic to liberalisation than the communists and the National Front, they would routinely oppose Rao in parliament – as always, short-term political gain trumped long-term principle. So Rao had to deal with the BJP. He did it by constantly briefing BJP leaders on reforms; he had many friends there – from Vajpayee to Shekhawat. Rao also ensured that the National Front and BJP rarely got together in parliament to oppose him. This is critical, since Rao was a minority in parliament. The biggest political opponent of reform, however, was his own Congress party. The way he out-maneuvered them is remarkable.

How was the equation between Narasimha Rao and Sonia Gandhi?

Until 1993 it was very respectful. Prime minister Rao would regularly brief Sonia Gandhi in person. He would defend each policy as being an extension of Rajiv’s vision, but he would never change the substance of the policies. In the first two years of Rao’s prime ministership, Mrs Gandhi was also too apolitical to interfere in politics. It was only after 1993 that Rao realised that he as PM did not have to report to Sonia. He did not do that, and she resented that. Also, the many Congress rivals of Rao would constantly go to 10 Janpath to complain about the PM. They deserve much blame for ruining the relationship between the two. After 1998, when Sonia came back to the Congress, she has ensured that Rao has been removed from the pantheon of Congress leaders. In the official Congress version of liberalisation, detailed on the website, Rao’s name is not even mentioned. I find that astonishing.

What would be your evaluation of Narasimha Rao’s contribution to the emergence of a new India and also the political system?

Rao is, in my opinion, the most consequential Indian prime minister since Nehru. He is also unique in world history for one reason: No world reformer brought about the kind of change he did with so little power. You can see his fingerprints on today’s India in so many ways. He altered the direction of India’s foreign policy, economic policy, welfare schemes, nuclear programme, and internal security. Subsequent PMs have broadly followed his direction. Almost every Indian family – no matter how poor, how marginalised – is better off after Rao than before. As I detail in Half-Lion, he had many flaws. But there is no question that he is the father of today’s India.

jasleen@governancenow.com

(The interview appears in the July 16-31, 2016 issue of Governance Now)