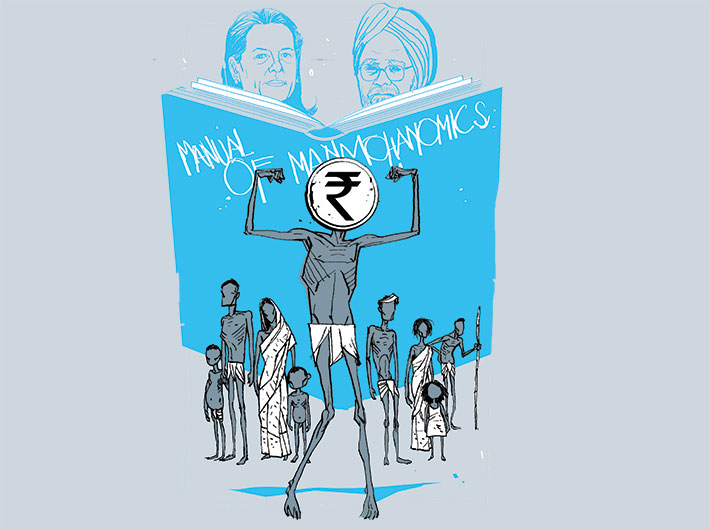

India has entered a vicious cycle in which policymakers won’t, and can’t, really think of the hungry millions often enough, and the rupee’s future is likely to give the finance minister sleepless nights

In the last few weeks, two issues related to the Indian economy have been in the headlines. One is the debate, not a very pleasant one at times, between two of the most famous economists India has produced, on the growth versus development question. The second is the sharp fall that the value of the rupee has experienced.

For a different view, read: Where's doom? Look at the silver linings

The Amartya Sen-Jagdish Bhagwati debate has also found its resonance in the discussions around the declining fortunes of the rupee. Many commentators have questioned the appropriateness of the government pushing the food security bill with its attendant fiscal implications at such a time of crisis. At the other end are critics of the government who consider the bill as reflective of a lack of intent – not doing enough, and less than what is possible, to address the problems of hunger and malnutrition. However, what can, and does, get somewhat obscured in the media debate on these issues is that the sliding rupee and India’s development shortcomings are mutually related outcomes of the growth trajectory of the last two decades.

The background to the current debates is the very real phenomenon that the growth that Indian economy has experienced over the last two decades or so has done very little to improve living conditions of the majority of Indians. Per capita income, adjusted for increases in prices has increased by more than two and a half times in this period – from a level that was already more than double of the figure at independence. These are of course still exceptionally low compared to other parts of the world. Nevertheless, people like Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze are right when they insist that not all India’s failures can be justified by merely the deficiency of resources. The scale of income poverty, hunger and malnutrition, lack of access to sanitation, healthcare and education, etc. characterising India today are way too high for that.

Clearly the quantum of resources required to bring about significant improvement in India’s social indicators in an arithmetic sense is not a very large proportion of the total available resources. At the same time, significant amount of resources are clearly expended on things that must clearly rank much lower in the order of social priorities. This kind of reasoning leads to the conclusion that the state has failed to ensure the best use of the resources created by economic growth. The question is: is this the only failure of the state, or is it only a particular symptom of a larger failure?

Somewhat paradoxically, it is also the inefficiency of the state which is invoked by those on the other side of the divide. Growth, they say, is important for generating the resources that can be expended on improving the conditions of the poor even as it itself lifts people out of poverty. It is then argued that the growth impetus of an economy is adversely affected by the inefficiencies that get created if the state tries to intervene excessively in the economy and fails to maintain its fiscal health. This leads to the assertion that instead of being myopic and spending excessively today, the society would be much better off in focusing attention on making the expenditures more efficient by plugging the leakages.

The levels of these expenditures, it is contended, would automatically increase faster if the pace of growth is maximised.

Economic growth vs development

The issue of the relationship between economic growth and development has been an old one in the field of development economics. This branch of economics dealing with the problems of what were called underdeveloped economies was initially born in the mid-20th century around the core idea that the state had to play a critical role in extricating such economies out of the “vicious circle of poverty”. Development, however, was more or less equated with the growth of per capita output and income. This was accompanied by a belief in the “trickle-down effect” and the perception that there existed a growth-equity trade-off in the initial stages of development.

Based on the observed historical experience till then, however, the idea that growth and development are practically synonymous came to be increasingly challenged in the 1970s.

Even as a measure of simply income growth – GNP or GDP – came to be viewed as a biased index in view of the fact that it reflected more the trends in incomes of the rich. In addition, it was argued, income increases of poor households did not automatically translate into better access to many basic needs and therefore public provisioning of services like health and education were important.

On the other hand, such provisioning itself would enhance human capacities and productivity, which would translate into positive effects on growth. All of these led to the view that the role of the state had to be more than simply promoting growth – it had to influence the nature of the growth process to ensure a wide distribution of its benefits and to ensure that sufficient resources are directed to the social sectors.

If we are today reliving in some senses an old debate, it is because of two facts. First, the dethronement of growth as the principal or sole development objective and the conception of an enlarged role of the state proved to be short-lived. Market-based ‘reforms’ were adopted, or forced upon, the entire developing world from the 1980s, and India too joined that group in 1991. In the worldview of economic liberalisation, the equation between growth and development was restored but it was now combined with the idea that the state had to withdraw from intervention in the economy.

The second fact is even more significant – the global experience over the last three decades has actually belied the belief that growth automatically translates into development. Indeed, even in advanced countries, like the US in particular, economic liberalisation has been associated with very sharp increases in inequality and income stagnation of the poorer sections of the population.

Exactly the same thing has happened here, with the added significant facts that the poor are a significantly larger section of the Indian population than in most other countries and their incomes are also considerably lower. In the last two decades, Indian growth has produced extreme levels of polarisation. But the corporate sector and corporate profits have grown as never before.

On the other side, even workers in factories owned and run by these corporations have experienced no increases in their wages in two decades, and this is symptomatic of a widespread phenomenon of income stagnation.

These beg the question: why has evidence from the world over and India, now considerably greater than what existed in the 1970s, not settled the debate once and for all? Instead, what we see is that not only is the state economic policy still tilted in favour of, mainly relying on market forces and the private sector, but even a narrowing of the debate on that policy, such that this core character of it is not questioned. This is where the argument that restricts itself to saying that the state has not done enough for the social sector falls short. It does not recognise the intrinsic connection between this failure and the growth strategy being pursued, and does not emphasise that alternative growth trajectories are possible.

The liberal growth strategy first gives rise to a highly inegalitarian growth process reliant on the profit-seeking ‘animal spirits’ of private capital. It then hopes to secure from these beneficiaries of growth process the resources the state can spend. However, if the animal spirits have to be preserved, the taxation burden must be moderate and when these spirits flag, or even otherwise, different types of concessions have to be given to prop them up. Thus, whether growth is rapid or slow, intrinsic limits are placed on the process of mobilisation of resources for spending on areas relevant for the majority.

At the same time, the inegalitarian distribution of income produces economic difficulties which work in the same direction. Its beneficiaries tend to spend on products and unproductive assets (like gold), which are more import-intensive in nature and contribute to balance of payment problems. At the same time, since the large majority does not have sufficient income to buy products that would flow from such investment, productive investments – like those on manufacturing activity – cannot be sustained.

Even exports of manufactures are hampered by the state being unable to invest sufficiently in building infrastructure. Adequate investments in other sectors like agriculture also do not take place because the incomes are not in the hands of those who could make these investments. An unbalanced growth therefore comes into being, which is prone to all the problems we see the Indian economy currently facing in combination – a growth (and particularly industrial growth) and investment slowdown, a large current account deficit and food price driven inflation. These are precisely the conditions underlying the fall in the value of the rupee. The danger to the rupee also prompts the government towards more concessions because it has to keep foreign investors happy so that they bring their money into India.

Thus, a vicious cycle gets created whereby no matter how much Professor Sen may urge it, it is not the hungry millions of India who will be remembered at most time by policymakers, and things like the future of the rupee are more likely to give the finance minister sleepless nights.

What’s wrong with Indian economy...

- Liberal growth strategy first gives rise to a highly inegalitarian growth process

- It relies on profit-seeking ‘animal spirits’ of private capital

- It then hopes to secure resources from owners of this capital to carry on the growth process

- But if the animal spirits is to be preserved, taxation burden must be moderate

- When this spirit flags, different types of concessions have to be given to prop them up

- So whether growth is rapid or slow, there are limits on resource mobilisation to spend on the ‘social sector’

- Thanks to inegalitarian distribution of income, the rich tend to spend on products and unproductive assets (like gold)

- These are more import-intensive and trigger balance of payment issues

- Since the majority lacks sufficient income to buy necessities, productive investments – like those on manufacturing activity – cannot be sustained

- With the exchequer not supporting adequate investment in infrastructure building, export of manufactures sets hampered

- Adequate investments in sectors like agriculture also do not take place because incomes are not in hands of those who could make these investments

- An unbalanced growth therefore comes into being

- All this has led to problems Indian economy is currently facing in combination: growth (particularly industrial growth) and investment slowdown, a large current account deficit and food price-driven inflation

- These conditions underline the fall in rupee’s value

- Danger to the rupee prompts govt to give more concessions to keep foreign investors, leading to a vicious cycle

...And PC’s solutions

Finance minister P Chidambaram presented his ministry’s report on the state of economy on August 27. Highlights:

RUPEE

- “Rupee will find its appropriate level, we have to be patient, firm and do whatever required. Rupee is undervalued, has overshot its true value.”

INVESTMENT PUSH

- PC is keen to get investment cycle restarted. “We are clearing projects, removing bottlenecks.”

- Cabinet committee on investment (CCI) clears 18 power projects worth Rs 83,772 crore. Banks have already disbursed Rs 30,000 crore to them. Fuel supply agreements for 18 power projects will be signed by September 6. CCI also clears nine other infrastructure projects involving an investment of Rs 92,541 crore. Thus, 30 percent of pending projects have been cleared. A day before, CCI cleared projects worth Rs 183,000 crore.

- Reliance Power’s Sasan project will receive stage-2 forest clearance.

-

LAND BILL NEXT

- After the passage of the food bill in the Lok Sabha, expect the land acquisition bill soon.