India is home to about 2,00,000 refugees, mostly religious minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. But the country is yet to have a national policy on asylum seekers, creating an awkward situation for Sikhs and Hindus who seek shelter in India from persecution abroad but do not get citizenship here.

Caught in-between

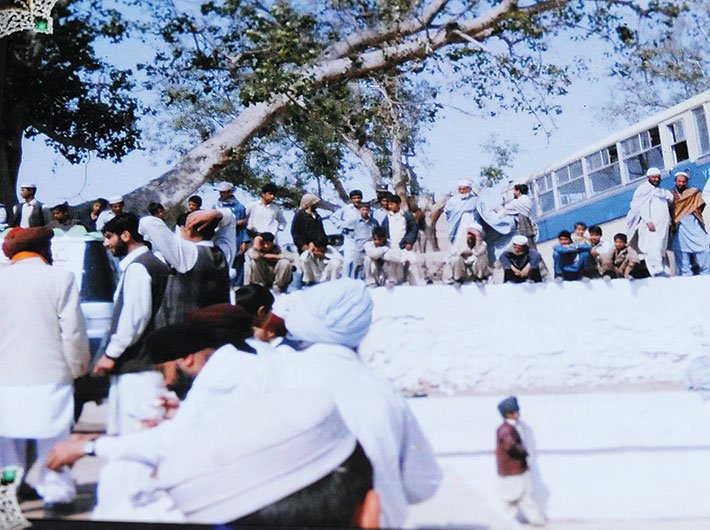

Within the narrow lanes of Delhi’s Tilak Nagar, in an airy room about 20 Hindu and Sikh refugees from Jalalabad town of Afghanistan are chatting among themselves. Their Afghan roots are immediately clear: the turbans are paired off with the typical pathani suit. This heritage streak becomes stronger when Manohar Singh Taneja starts speaking. His Punjabi still has the rough sounds of the mountains.

Taneja is the president of Khalsa Diwan, an organisation dedicated to helping the Hindu/Sikh refugees from Afghanistan. He is also a man who no longer has a country – he has been without one for two decades. He has found that the Indian government does not grant citizenship easily.

“In all these years, the Indian government has not helped us with even a single paisa. All we want is our identity,” Taneja says. He belongs to a group of Hindu and Sikhs whose ancestors had migrated to Afghanistan, participated in the country’s growth but had to flee it when tensions started. Today only about 5,000 Hindus and Sikhs remain in Afghanistan.

As Afghani citizens, when they returned to India, they applied for citizenship under the Citizenship Act. With luck not on their side, the government made changes in the rules of citizenship twice – extending the number of years that a person needs to stay in India legally before he or she can apply for citizenship; first from 10 to 12 years and later to 14 years. Two decades have gone by, yet they remain without a country.

READ: How India responded to the influx of 10 million refugees

Taneja says, “In 2009, the Indian government made certain changes in the law due to which the citizenship process came to a stop. One of the main conditions for this was that the applicant’s existing passport should be renewed. And the Afghani embassy has its own rules.” The group has approached the home ministry, the FRRO [foreigner regional registration office] but it has resulted in nothing. “They harass us. They ask us all – young children, old and sick people – to come to the office,” adds Taneja.

It is with an air of nostalgia that Kuldip Kumar, a Hindu refugee who came to India in 1993, remembers his wonderful life in Afghanistan. If there were no religious persecution after the advent of the Taliban on the scene, he swears, they would never have left their ‘homeland’.

“We had large businesses there. Some of us traded dry fruits; others ran a clothing business or medicine shops. At one point of time, Hindus and Sikhs were responsible for 50 percent of Afghanistan’s growth. We had houses (of roughly 5,000 yards) that were triple in size of the houses here. We left money in our bank accounts and fled. We just had to save our lives.” The properties were then taken over by locals - in some cases by warlords. Others had to dispose off their properties at throwaway prices - equivalent to 10 percent of the market price - and were asked to leave.

Highlighting the huge gap between the life in Afghanistan and the life they have here, Taneja says, “We have not experienced anything close to the good life we had in Jalalabad. We have been in India for so long , yet we do not have any documents to prove that we are Indian citizens.”

The struggle to find a new home has forced this group to question their own identity. The taunts have come from both sides. While the Indians call them “Afghanis”, back in Afghanistan there are many epithets. “They call us ‘Hindi’, and ‘kafir’. Even if somebody from our community does anything good, the locals say that had we been Muslims it would be better,” Taneja says.

Complaints of religious discrimination do not stop there. Both Singh and Kumar say that even the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had discriminated against them on the basis of religion.

Taneja says when the refugees came from Afghanistan, majority of the Muslims were resettled in a third country. The Hindus and Sikhs were told to stay back in India.

“At that time, there were about 60,000-70,000 refugees with long-term certificates for stay. Today, there are only 25,000 people left. So what happened to the rest? The UN helped them settle outside, and left us on our own. We were told that this is your country. Your parents were from this place. They left and now you have come back. The western countries refused to take us and the UN did not pressurise them. But if the Indian government does not support us, how can we call it our own country?” asks Taneja.

He, however, takes a broader view of things. “We also realise that when the Indian government is not able to give basic amenities to its own people, how will it take care of us?”

In aid of asylum seekers

There are 31,000 registered refugees. The UNHCR has been helping them in collaboration with the government. The understanding is that while the government will deal with refugees from the neighbouring countries, including Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, the UN body will deal with refugees from the non-neighbouring countries except Myanmar.

UNHCR facilitates proper documentation for the refugees and asylum seekers to help them stay in India. Lawyers provided by UNHCR verify the status of the refugees. Then the asylum seekers have to approach the government in order to receive the long-term certificates.

However, this is a longish process and takes about four months. In the intervening period, the FRRO provides a ‘stay visa’ that ensures they are not being detained for illegal stay. In turn, the long-term certificates help the asylum seekers in finding jobs and getting mobile SIM cards.

UNHCR also works with NGOs like Bosco and Slick to provide a dignified life to the asylum seekers. The NGOs help the asylum seekers in getting admission in government schools, learn languages and even access medical facilities.

“The children who come from places like Kabul lag behind in terms of education. These organisations provide classes so that their education levels can come up to a certain standard,” says Shuchita Mehta, senior communications officer, UNHCR, New Delhi.

The UN body also doles out cash in some cases. Mehta says, “UNHCR provides limited financial assistance to the most vulnerable refugees, which is however designed as a time-limited support and it does not constitute an entitlement.”

She explains that the UNHCR conducts individual interviews to determine the refugee status and issues documentation to asylum seekers and refugees. These papers are usually accepted by various authorities and save the refugees from being detained or arrested for illegal stay.

On paper, all refugees in India have access to government health and education services but given the rush there, it’s a harrowing task for the refugees to avail these. “The UNHCR along with its partner NGOs help them get access there,’’ Mehta says.

With the rise in the number of refugees across the world, the UNHCR has proposed three options for the asylum seekers. The first is local internalisation, wherein the refugees are encouraged to become a part of the local society and begin a life anew, like the Sikh Afghani refugees in India. About 800 Sikh refugees are currently residing in India.

The second option is to send the refugees back to their original country once the situation improves there. The Sri Lankan refugees are the best example of this.

The third and last option is to rehabilitate the asylum seekers in a third country. This is a rare option, and less than two percent of the refugees have been rehabilitated this way. Each country has a quota of the number of refugees they can take from each country. Currently, the Indian office of the UNHCR has 4,000 applications under process.

No law, no policy

In spite of the huge influx of refugees into India, New Delhi lacks clarity as to how to deal with them. It neither has a national policy nor has it signed the 1951 UN Refugee Convention.

However, UNHCR officials are all praise for India’s handling of the refugees.

Mehta says, “India has over the years hosted waves of refugees and has demonstrated its commitment to refugee protection and adherence to Article 14 of the Universal Declaration for Human Rights (The Right to seek and enjoy asylum). Additionally, India has developed positive and inclusive administrative practices that uphold the fundamental human rights of refugees.’’

Throughout history, India has been generous to those seeking protection from persecution. Even without a formal refugee law in place, India recognises the status determination undertaken by UNHCR with regard to individual refugees who have presented themselves,” says the official.

Notwithstanding the absence of a national policy, India has occasionally made country- and group-specific laws on refugees. For example, the Modi government recently decided to exempt the non-Muslim Bangladeshi and Pakistani nationals from the condition of 14-year mandatory stay in India for citizenship.

This will enable hundreds of Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Parsis and Buddhists, who were compelled to seek shelter in India due to religious persecution in other south Asian countries, to become Indian citizens. This decision, however, has come under attack from people alleging the citizenship on the basis of religion would set up a wrong precedent.

ankita@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the October 1-15, 2015 issue)