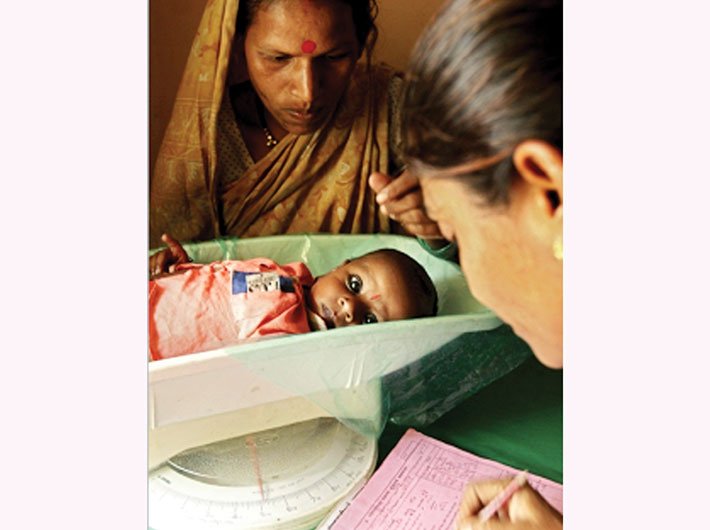

Malnourished children, the shame of India, are more common among the marginalised groups like dalits

With the Rajya Sabha TV into its second rerun of the Samvidhan serial and the constitutional debates on affirmative action and Dr BR Ambedkar’s resolute stand playing out in our living rooms, it is good time to take a long, hard look at the outcome of affirmative action for the excluded groups. With a new prime minister who claims to hail from a marginalised caste, the timing couldn’t be better.

A study supported the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition has examined the status of under-nutrition and its determinants among the dalits. Also under scanner were the policies, programmes and legislation meant for dalits (scheduled castes, or SCs) and improving their nutrition status.

Why nutrition? Well, because it is a composite tip-of-the-iceberg indicator for many things working well, like healthcare, food security, education, water sanitation and social protection, as the Lancet journal pointed out in its special nutrition issue in June 2013. Also because, India, the second fastest growing economy not so long ago, has been stuck with seabed level under-nutrition figures at 46% – almost double the burden of sub-Saharan Africa.

Dalit under-nutrition cannot be decoupled from the story of caste-based discrimination and marginalisation and the increasing political resurgence of dalits in recent past. The performance of the marginalised constituencies, dalits, adivasis (scheduled tribes, or STs), Muslims and others, is an apt litmus test of the government’s sincerity towards the most vulnerable groups and effectiveness of its programmes and policies for them.

A long away from catching up

An exercise of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) reanalysis suggests that 53.6% of dalit children are malnourished (moderate and severe acute malnutrition) compared to the general category children at 39.2% and the all-India average of 48.4% as per NFHS 3. While the decrease in severe acute malnourished is at 3%, the moderately malnourished amongst the dalit children has increased by 3.4%, negating the overall improvement since NFHS 2. As per NFHS 2, while the total malnourished children among dalits were at 53.5%, the figure has worsened marginally to 53.6% by NFHS 3.

Forty-eight percent dalit children are stunted compared to the average of 35.6% for general category children and 43% for the all-India average. The 13% additional stunting prevalence among dalit children and similar figures among adivasi children worsens the all-India average, and hence require specific action.

Only 13.89% dalit households have piped water supply in their residence, plot or yard, compared to 27.51% among the general category. There was a limitation in NFHS 3 that it did not provide data for hand-pump into residence, plot or yard and it seems that it was merged with ‘public tap/hand-pump’. So, performance and trend vis-à-vis NFHS 2 is difficult to state. In this case it would be more significant to say that 86% of dalit households were not getting piped water supply as per NFHS 3. This is a major concern considering most habitat-level discriminations as well as hygiene and pollution factors play out via water (access, inaccess and restricted access to it). As a counter, increasingly confident and affirmative dalit youths are also affirming their dignity via water access, reversing practices of purity and pollution.

One-fifth of dalit mothers of underweight children can decide on their own how to spend money, which is 7% less than the general category mothers with children who were underweight. Between NFHS 2 and NFHS 3, autonomy in terms of decision-making for spending money and seeking health care has shifted heavily from solely the partner’s domain to “jointly with partner”, which is a good development. Though dalit women have more economic engagement than general category women, almost 60% of women were not allowed to have money for her own use, which means brahminical patriarchy was also rearing its head among dalit households.

It is clearly evident that a majority of children at the time of birth have average or larger than average size, and deprivation-based growth differences kicks in much later than in mother’s womb. It is the socio-political adversities which make them underweight, wasted or stunted during their initial years of life. The state’s role needs to be questioned here, both in service provisioning and political will.

Coupled with the fact that the WHO’s global growth monitoring anthropometric standards were set up through an elaborate six-country exercise, where India was also a case study, means Indian children’s anthropometric failures have more to do with public policy and social challenges than genetic programming.

During NFHS 2 it became evident that family planning workers were not visiting households across all sections of society. And the visits were not significantly different between households with normal children vis-à-vis households with underweight children. However, this question has changed in NHFS 3 to ‘visits by auxiliary nurse midwife/lady health volunteer and anganwadi worker’, so they cannot be compared with NFHS 2.

But it is important to note that for underweight children the anganwadi workers are paying fewer visits to the households of all categories, including dalits. Home visit figures are extremely low and that is a matter of concern. Visit (or lack of it) to the pregnant women or child-bearing households is also where discrimination by frontline staff can and does easily play out.

Common sense says that prevalence of underweight children in poor households is higher. However, the conflation of poverty (low standard of living) and underweight children is considerably higher among dalits at 49.1%, which goes much higher to 56.8% for adivasis. For the general category it is much less at 25.8% and the all-India average is 37.5%. Again, this is a statistic made considerably worse at the national level because of the adverse performance among the dalits and adivasi poor households and under-nutrition prevalence, which clearly points to the necessity of state intervention.

In summary, a rigorous reanalysis shows that while the performance of nutrition indicators among dalits is improving, it is nowhere near the catch-up pace. It is lower than the general category performance. Under-performance of nutrition indicators among the marginalised population categories is a double whammy: on one hand it is pulling down the all-India averages and on the other, till catch-up happens, the anthropometric inequalities and its consequent impact on learning and earning will also persist.

The state response: resources, legislations and allocations

The state response has been predictable. It denied the harsh reality, and even shot the messenger by discontinuing the NFHS exercise because the survey findings brought bad news. The NFHS 3 concluded in 2005 and the next NFHS is only now, over 2014-15, after much lobbying and advocacy.

But many progressive legislations and programmes for reaching the unreached among dalits and adivasis cannot be denied either, especially the ones authored by the father of our constitution and the subsequent improvements via legislations.

Key constitutional provisions have been nothing short of inspirational, from Article 14 on equality, Article 16 on equality of opportunities, Article 17 on abolition of untouchability, Article 21 on right to life, Article 46 on promotion of educational and economic interests, and Article 47 on nutrition to a host of provisions on adequate representation of the dalits and Article 271(1) on additional special central assistance via special component plan (SCP).

The SCP, initiated during the sixth five-year plan (1980-85), envisaged a radical redefinition of planning and budgeting for dalits. It was based on the realisation that decades of planning and hundreds of millions of rupees spent in the name of welfare of SCs and STs had not brought any substantial changes in their socio-economic conditions. Hence, the SCP was brought in as a radically reworked strategy of dalit welfare and empowerment.

As the SCP mission statement notes, “The sixth five-year plan marked a shift in the approach to the development of the SCs. The SCP, launched for the SCs, was expected to facilitate easy convergence and pooling of resources from all the other development sectors in proportion to the population of SCs and monitoring of various development programmes for the benefit of SCs”.

This meant, in practice, that the Centre has to set aside 16.8% (the SC population as per 2011 census) of its annual planned budget for uplifting the economic, social and human development status of dalits. This is to be provided to the states and respective line departments based on their plans for dalits, and it is pooled at the state capital and submitted to the union finance ministry and the planning commission. Every state can demand as a matter of right the percentage allocation from SCP based on its dalit population. It is meant to top up the state and departmental resources since it works with the progressive and pragmatic rubric that reaching the unreached and marginalised costs additional money.

Additionally, there has been monitoring of discrimination in public-funded food and nutrition programmes. The human resource development ministry’s mid-day meal scheme deserves a special mention because it not only emphasises on active monitoring of acts of discrimination, but it has also taken the good practices like mandating dalit cooks, and show-cased and scaled them up. The result has been mixed, from radically progressive measures to dilution of the very basic elements. In case of Andhra Pradesh, they have mandated dalit cooks to engineer social cohesion and camaraderie amongst children early.

The policies, programmes and allocations, drawing from Ambedkar, are nothing short of revolutionary and imaginative, but the erosion happens in the operationalisation and last-mile delivery of programmes.

Eroding rights: under the radar but subverting the progressive spirit

We know that rights won through people’s movements, transformative social reforms processes and progressive legislations are easily lost if not backed by programmes and resources, capacitated institutions and committed staff to deliver the same and a vigilant citizenry to monitor it. Unfortunately, affirmative programming for dalits and other excluded groups are sometimes a meta-narrative of the same. Some of the challenges which pose a danger to the rights and entitlements scripted in all these policies, provisions and programmes are manifested in state lethargy, tardy implementation and downright violations at the grassroots. This makes resistance even more difficult, considering the violations escape official scrutiny but unfold via lived realities and indignities. Worrying instances have been many but some stand out, such as:

As an outcome of Sukhdeo Thorat and Joel Lee’s work on gross absence of public feeding sites and institutions in dalit and other excluded groups’ hamlets resulting in their deprivation and exclusion, the supreme court mandated in 2003-04 that all habitats with over 30% dalit or adivasi population get anganwadi centres on priority. The implementation has been at glacial pace.

Same was the mandate for the MGNREGA work generation – on priority for the excluded communities. Predictably that hasn’t taken off either.

While the social justice and empowerment ministry claimed that 139 special courts had been set up to prosecute untouchability and atrocities, grassroots dalit activists writing shadow reports say the truth about the number of courts was much less encouraging.

But the worst subversion has happened in case of additional central assistance for dalits and adivasis via SCP and tribal sub-plan (TSP) respectively. A progressive provision expressly meant for enhancing the socio-economic conditions of dalits and adivasis by providing states with additional resources, pro-rata with the population of the excluded communities, has been siphoned for constructions, road and capital city refurbishments and other varieties of activities which have no relation (direct or oblique) to dalit and adivasi upliftment.

A provision meant for topping up limited state resources for the most marginalised constituencies has been switched by many states for profligate heads. What makes it worse is the creative accounting they resort to to still claim on paper that these siphoning or switching is resulting in enhancement of the dalits’ and adivasis’ status. It is almost as if some states are at war with their weakest!

But there have been glorious exceptions too. For example, Andhra Pradesh has legislated the SCP and TSP assistance, ring-fencing the resources for the populace it is meant to serve.

Righting wrongs: reclaiming affirmative action

While the programmatic and institutional challenges are many, all is not lost. Other than the federal policies, provisions and constitutional guarantees, committed civil society organisations and resurgent dalit movements are challenging the norm and scripting success. Most of the NGOs with visible impact and models have a strong component of engagement with the state system. They have also worked on community awareness, behaviour change and change-agents model. Almost all civil society organisations which have demonstrated impact insist that working on empowerment, with local community and governance structures in a rights and entitlements framework is an essential component. But the importance of fostering a zero-tolerance to discrimination and building a society where fault-lines of caste are eroded soon is the absolute first step.

There has been a clamour for better data and more investment in data generation, but the research has faced multiple hurdles. For example, dis-aggregations collected were not being disseminated, raw data was being released much later when they almost became irrelevant and were not feeding policy or programmes and questions in periodic surveys were changing making comparisons and trend analysis difficult. For starters, dis-aggregation of data collected on identity groups needs to be published and disseminated. This is the minimum public-funded surveys should do, that is, reveal the performance of excluded and marginalised groups on various human development indicators.

Locating nutrition in the context of institutional governance, especially for the marginalised communities, is equally important and it can be done via embedding voice, visibility mechanisms, challenging elite capture and programming with politics and power as determinants and not just technical fixes.

Equally important is investing in building planning capacity at the state, district and sub-district levels for SCP, micro-level plans and monitoring their implementation. This could be done via inclusive programming.

Closing the research gap is equally important. Too much research investments are on policy level rather than operational challenges and programming, planning deficits. This misplaced research priority needs to be corrected.

A very progressive provision like the SCP and TSP has been reduced to arithmetic exercise, switching finances, rather than topping them up. Andhra Pradesh has enacted a legislation to ensure SCSP and TSP are implemented in letter and spirit. Nationally a coalition of dalits and adivasis is pushing for the same agenda. Supporting to enact a legislation which ensures marginalised communities and their habitats, especially dalits and adivasis, get additional finance, build their local planning capacities and script their development plans, requires joining forces. This is a worthy agenda to support, not just for nutrition actors, but social justice advocates. Considering how social justice is intertwined with nutrition, this definitely calls for investments from nutrition actors too.

Demand-side pressure has been celebrated as the silver bullet to build a responsive system. This calls for resource investments at grassroots level to build a cadre of dalit and adivasi leaders, aware of their entitlements, from the nutrition sector and its determinant sectors and exert pressure on the public service delivery mechanism to make it deliver for the poor and marginalised, every single time. Investing in building such models in some of the caste/deprivation entrenched areas and tracking the transformation and the change would go a long way in establishing a real feasible model and its impact on people and services.

Swain works on poverty, public policy and citizen-state engagement in South Asia and Horn-East and Central Africa. She is also an adjunct faculty at the UNESCO-MISARC, Pondicherry Central University and Swedish University of Development and Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala. Her research interests are the inter-sectionality of food-nutrition and agriculture and the political economy of essential services. She led the research. biraj_swain@hotmail.com

The data re-analysis has been done by Dr Singh. He is a PhD in public health from JNU with interests in health equity and spatial distribution of facilities. He is associated with South Asia Dialogue for Ecology and Development (SADED). ranvirjnu@gmail.com

(The story appeared in the August 1-15, 2014 issue of the magazine)