Opposite gate number two of Jama Masjid is the Urdu Park. A short walk to its main gate is along a row of hawkers selling winter wear and shoes on pavement. The park, large enough for a football match, has two tin shelters – one each for women and children. A third one – a tent – is being set up to house men.

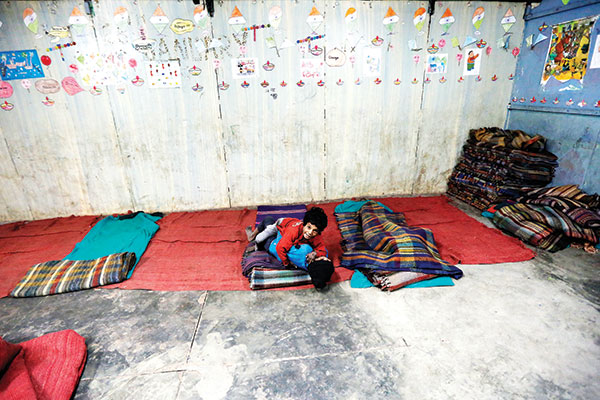

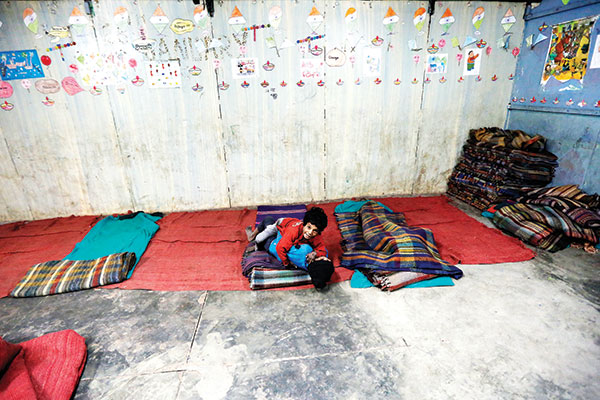

We first enter the children’s accommodation, meant to shelter 50. Two kids, dressed in dust from head to toe, are busy playing marbles. The tin gives us cold vibes but, surprisingly, it is pretty warm inside. Some efforts have gone into this. The floor is cemented and walls are covered with thermocol and a plastic sheet. Bubble wraps have been stuck on the ceiling and jute mats laid on the floor. The worn-out mats are covered by durries for extra insulation against the cold coming from the cement.

Blankets are stacked in a corner. As you lift one it releases a cloud of dust; the kids are way too busy to worry about this. A modest TV set with a branded set top box, kept on a stool, is yet to be switched on. Crayon drawings of dogs, cats, birds, Indian flag, smileys, etc. pasted on the walls liven up the place.

Ashok Pandey of Beghar Foundation, the NGO operating the shelter, inspects the men’s tent. “The situation has improved considerably over the years, especially this year. The space is less though,” he says. Pandey had lived on the footpaths of Old Delhi for 12 years. “I can understand their problem as I have gone through the pain which thousands suffer daily,” he says.

We notice a missing-child poster on the door of the children’s shelter. “Many a time, parents feel that their missing kids might have wandered at these shelters. Hence, the poster,” says Pandey. One of his colleagues comes hurriedly to offer Pandey a woollen jacket. He puts it on realising that he is now shivering.

About 100 metres away from the park, there are more shelters.

To reach there one has to wade through a poorly-lit parking lot which doubles up as idling place for locals, especially the youth. This one is congested – three tin shelters, one each for men, women and families; and two tents each for men, all located in a smaller ground. Inside the fenced boundary one has to walk carefully to dodge patches of mud. A hint of illumination coming from distant street lights helps. Close to the Delhi jal board water tanker, the legs of which are mired in sludge, volunteers of Beghar Foundation are busy readying a new shelter.

Twenty two-year-old Khushi is working as a caretaker at men’s tents. Khushi’s job is close to her heart as it was here that she had found her soul-mate two years ago. In fact, she even got married inside one of the shelters. Khushi says she and other caretakers have to deal with the problem of more people and less space every day. “On some days, it gets so crowded that women are forced to sit the whole night. Once I had to sleep holding my ten-month-old son on my chest. But we try to ensure that no woman spends the night outside,” she says, shooing away a stray pup who comes to nibble her feet.

Near the tin shelter, meanwhile, a middle-aged man lights up a bidi, ignoring the no-smoking rule. Another man, probably mentally challenged, sits outside against the wall of a tin shelter.

It is 9 pm and we go looking for a place to eat in the nearby market. Some 45 minutes later, as we walk back to the shelters, we end up disturbing a man who is getting ready to sleep. Mohammad Ayub and his friend are about to sleep on a rehri or pushcart, which during the day doubles up as mobile fruit shop for him. The rehri-cum-bed is perched along the wall of the parking lot.

The two manage to make space for each other on the makeshift bed. They have a woollen blanket for cover. Peeking from the blanket to speak to us, Ayub says, “We have no option but to sleep here. We cannot sleep inside [the shelter] as we can’t take our belongings inside and they can get stolen. Moreover, there are drunkards sleeping inside; who would want to go there?” Ayub, who hails from Uttar Pradesh, has been living in Delhi for 18 years. He has been sleeping on the streets every night, be it winter or rains. After talking to us, Ayub withdraws his face inside the blanket.

At 10, we return to Urdu Park to check on the men’s shelter. The tent is finally ready, inside on the bare soil wooden beds are placed in a row. It is quite warm inside but the dust-laden still air is troublesome. Only three men are snuggled inside the blankets, though there is room for 30. Wasim, Noor and Shahrukh, all in their early 20s, work as helpers at weddings and also do odd jobs. They had been sleeping in the open until today – when they come to know about this shelter. “Outside, we have to pay as much as '40 for one blanket. Here it is free,” says a beaming Noor.

The women’s shelter next door is quite full. Forty-year-old Bhano is a regular here. Her 12-year-old son too sleeps at the children’s shelter in the same park. “I reach here at most by 9 to confirm a place; otherwise it gets difficult to get an entry.” She does not really have complaints but wishes that hot water was available. “In the chilly mornings it is tough for children to take a bath or wash their face with cold water,” she says.

The others, around 40, seem too busy to pay us any attention. They do not want to miss any action of the soap playing on the TV set. People taking shelter here can watch TV till 10.30, though on weekends the informal deadline extends to 11. We move back to the shelters ahead of the parking lot. Here, more groups of men are now hanging around. At one of the shelters, a young man, apparently drunk, is quarrelling with the woman caretaker. It seems that about a week ago, he had informally deposited '270 with her to collect it the next day. However, he could return only today. When he asked for his money the caretaker claimed that he had already taken it. The fight continues for the next half an hour, and perhaps even after we left.

In the narrow lanes of Jama Masjid, Mohammad Sayeed and his homeless neighbour Bismillah Khatum squat beside a bonfire made of wood briquettes. Sayeed, 30, lives on the streets with his wife and three kids. He once tried visiting the nearby shelters but did not have a good experience. He claims that the entry is mostly for regulars only. “Apart from the monopoly, many drunkards hog the shelters and use foul language. We are family folks, we can’t go in there,” he says.

As we struggle to maintain our squatting position, Khatum offers us a half-brick for a chair.

Ironically, Sayeed owns a house in Delhi, where his mother lives alone. Being a rickshaw puller, Sayeed believes he can earn good money in the centre of the old city. As his home is located some 35 km away, commutation is expensive and time-taking. No wonder, his face wears a sad countenance.

Khatum, 50, who works as a maid, says that renting out blankets has become a big business in the season. “Rates vary between '20 and 40 per night. Thankfully, I have my own,” she says, still shivering.

The fire is dying out as the last trails of smoke billow from the bonfire. Sayeed and Khatum stand up; spread out their blankets signalling an end to our conversation.

Suhana pops her head out of one of the 40 grey-striped blankets that fill the room for women without homes near Nizamuddin dargah. It is a chilly night in the city. Suhana first takes her eyes out of the layers of warmth she has hidden herself under. Her curious eyes search for acceptance, a smile, perhaps. Once confirmed, the hesitation disappears. Her right hand stretches out. Blue and grey gloves cover her rough, worn-out hands, which she shows later in the conversation to flaunt her rings studded with cheap gems.

Between the donated gloves and the cream sweater, an array of colours shines bright. Green glass bangles have a few misarranged maroon ones. A dozen bought for '20. A thick gold coloured metal kada is adjusted at the end of the glass bangles in each wrist. “I bought these for '120 each from the bazaar,” she says, turning the kadas to show the intricate flower patterns on them. The colours on her wrist match the colours on her saree.

She is now sitting upright in her bed made of a fluffy mattress, a bundle of clothes wrapped in the shape of a pillow and layers of blankets. “I saw you come in earlier,” she says to explain why she is still awake. Her smile deepens the countless wrinkles on her face. She does not know how old she is; we think she should be in her 60s.

It is 11 and quite late for women at the night shelter, except for Suhana and a few other late sleepers. Most other women have retired for the night, oblivious of the blaring LCD TV set in the large room. A young man in the daily soap is reminding a weeping woman that she should forget about the man she loves and fulfil her duty as a wife to the man she is married. Just then, a woman in her early 20s suddenly enters the shelter. She is howling and crashes on the mattresses next to two women who are watching TV in the row opposite to where Suhana has laid her bed. She fought with her husband and has come running to the shelter from her shack outside. “Her husband eats from what she earns yet disrespects her,” one woman tells us. The TV is gripping. The tears stop flowing.

Suhana barely notices the young woman, or the TV. In the shelter, her world stretches only till her mattress, not beyond. We are sitting on her mattress, a part of her world at the moment. “I make no friends,” she says, her eyelids open wide and her hands touch her ears. “Mera sirf allah hai,” she says, pointing a finger to the sky and holding the pose for a few seconds. Her smile returns, and so do the wrinkles.

Does she have a family? Where is her husband? What about her children? “Main tanha akeli,” her colourful wrists roll in perfect circular motions. Many a time, her hands reach out to her forehead to stuff the lining of silver hair back inside the hood of the cream sweater. She has spent a long life alone. “I had some friends. We used to live together. Then I left them. I don’t know where they are.” This is all the family she ever had. “Ab aap meri, main tumhari,” she says, her lips curve again. Her days are now spent outside the dargah, the nights at this shelter across the road from the dargah.

For one month now, this rectangular tin cabin or porta cabin, called rain basera, is her comfortable refuge from the world, even though she is surrounded by women and children every night here. She gets free meals here. If she doesn’t sleep in the cabin, she asks for food from the several eateries that line the dargah. She manages somehow.

The colours on the cabin walls are like colours on Suhana. A lining of thin PVC sheet covers the cabin from inside. Big flowers are painted on two longer sides. The wall behind the TV has happy faces. The one opposite is hidden by a black board, a white board and the caretaker’s table. The ventilator above the happy faces is turning the room smoky. The two caretakers have a house in the open space lining the porta cabin. They have lit a fire. The smoke rising from it fills the cabin. The air in the cabin smells of smoke. But Suhana doesn’t bother. Nobody bothers.

The air thickens and the caretaker, when prompted, gets up to open the metal windows with frames painted blue. These were loosely shut to keep the chill out. The doors are open. The lights are on but 40-year-old Mobina is tucked in her bed at the end of the row where Suhana is sleeping. Like Suhana, she is here alone. She doesn’t know who is sleeping next to her and she doesn’t want to know.

Mobina is in Delhi all by herself for her three daughters whom she has left with her mother in Kolkata. When Mobina’s husband died few years ago, she came to Delhi in search of work. She tells me her story as plainly as she looks right now. Her face, neck and hands are out of the blanket. Her eyes have no kajal. Her nose has no nose ring. Her ears have no earrings. Her fingers have no rings. Her wrists have no bangles. Her only possessions are a few pairs of clothes and a small pouch for money. The more valuable of the two is tucked inside her kurta.

She works at a private hospital in Ashram locality and earns '5,000 a month. Which just about equals a room’s rent in Delhi. “I have been sleeping here for the last three years,” she says. She sends '3,000 to her mother. Out of the remaining '2,000, she spends on bus journey to work. Her pouch has old bus tickets and her new mobile number scribbled on a tiny piece of paper. She has not memorised her new number yet.

The whining of women in the daily soap turns to loud arguments on Big Boss, the reality show. Six women are awake in the room now. The lights are still on. Mattresses line the two longer sides of the cabin. Traces of red durry can be seen in the row laid in the middle of the room to add extra beds.

“If more women come at night, then the durry will be spread right till the end,” Nazma Khatun Ansari says pointing at the middle row of beds. Nazma has completed a year at this shelter. A pink pajama for babies is drying on a bundle of clothes tied in a dupatta next to her. Her five-month-old daughter, Alfa, is hidden under the blankets. Alfa was born here, she tells me. “The caretakers called the ambulance and brought me back after delivery,” Nazma says.

Before she moved to the shelter, she was living on the pavements near the dargah with her husband. Earlier, she had a home. When her husband was detected with tuberculosis, his joint family threw them out. With the illness, he could not work. With no income, they could rent no room.

“I was with him till he died,” Nazma narrates the sequence of events with a stony face. She was two months pregnant then. She decided to move to the shelter once she was left to fend for herself. Moving to a shelter when her husband was alive was not an option. “There are no shelters for family. They are either for women or for men,” she says. “A woman who has lost her husband has no one to support her,” her eyes on the stony face moisten and dry in no time.

A plastic tent is erected by the Delhi urban shelter improvement board (DUSIB), a state government agency, a few steps away on loose rocks. It is a family tent, without any partitions. “The surface will be levelled and people can start sleeping here from tomorrow night,” says Abdul Gafar, the caretaker. But it is of no use to Nazma now.

In her work as a construction worker, Nazma prefers security over more money. For non-permanent work, which means she has to find work every morning, she is paid Rs 350 to Rs 400 per day. For permanent work, which means she works every day for the same contractor, she gets Rs 250 per day. “I prefer permanent work. Even though I get less, but there is job security so I don’t even ask for more money,” she says.

The night shelter provides her all the comforts she needs. For breakfast, she gets tea and biscuits (children, who sleep in an adjoining, equally colourful shelter, get bread, eggs, cornflakes, milk, tea, jam – something different every day). For lunch she gets dal, rice and vegetables and dinner is dal, chapatti and rice. “I am not saying all this because you are here today,” she explains.

The children will get bread tomorrow. The loaves have already arrived and rest on the caretaker’s desk.

It is festival time at the dargah. Fewer women will come to the shelter today. Nazma doesn’t talk to women around, but she has been observing. “Most of the women stay near the dargah during festivals. People come and donate food, clothes and blankets,” she says. On other days, the shelter fills beyond its capacity.

For the past week, Tara, the caretaker, has registered more than 60 women every night. In November, the numbers were low, at about 40. The shelter is built for 50. “As the temperature dips, as many as 100 women sleep inside,” Tara says. “Women join mattresses and make more space but no woman is left to sleep outside in the cold,” she says.

Behind the newly erected family tent, small fires burn here and there. The flames light the surroundings to show shacks standing on broken wooden and metal pieces, and anything that stands upright and can hold plastic sheets. These are homes for over 250 families; some have as many as 14 members. The shacks barely keep the cold away but no one living inside them will ever go to the sturdy tin shelter steps away. “We have a home. It [the shelter] is for those who sleep on the road,” says one of the women huddled near the fire. A baby sleeping in her lap is easy to miss. Within a year, the shacks have gone up from 20-odd to 250, the locals tell me.

On the footpath outside the shelter, a couple is sitting close to a small fire next to their home. Their home is a plastic sheet for ceiling and no walls. At the bus stop, under its bright white light, a man is preparing to retire for the night. He puts some clothes on his crutch to make a pillow.

Small fires burn everywhere. One such fire is burning in the space between uneven trees growing on the side of a pavement on Lodhi road, under the Oberoi flyover. Three men and a woman sit around it on broken ceramic bricks and pieces of wood hammered together to form a stool. No words are exchanged between them. There is commotion as we approach them, but nobody answers our questions. They don’t tell us if they will talk to us.

We try to make them at ease, but someone else wants our attention badly. Their Labrador will not let us go any further unless he is patted. Wearing a brand-new red dog coat, he is standing between us and wants to be acknowledged. His tail is wagging too fast and in no time he pounces on one of us, a loving gesture. His name is Doggy.

The youngest of the three men points a finger to the side of the short ledge where a few bricks are broken. We should come in from there, he is trying to tell us. The woman, meanwhile, manages to bring a rickshaw puller near the fireplace. Mohammad Sohail Rana, the rickshaw puller, does the talking for them. He is their neighbour. Five of them live together under the uneven trees there. “He sleeps here,” Rana points at the small man smiling and warming his hands at the fireplace and then at his spot under a tree. “And I sleep under this tree,” he shows us his spot.

As we take our spots around the fire, Doggy comes and sits next to us. He comfortably rests his right leg on one of us, as if a long-time friend. The first few minutes, we try to figure out their names. They cannot speak words and we cannot understand sign language. The woman has an idea. Like Mobina, she pulls out her most precious belongings from her kurta. Her voter ID card has her name – Julekha – and she is 42. Her small plastic pouch has the young man’s voter ID card as well. He is Shahil and is 32.

Are they a couple? They don’t meet our eyes. Embarrassed, the woman looks blankly at the plastic pouch that has a few other papers. Julekha and Shahil share a space under a plastic sheet that is supported by the ledge and bricks on side and only bricks on the other end. They have a common chulha and a kitchen garden. Shahil takes us to show his kitchen garden where he grows chillies, his favourite. They grow big, he signals and cannot stop giggling. The tiny nursery is protected by small wooden sticks acting as fence that are tied together with wire. A papaya tree, vines supporting varieties of gouds – tori, lauki, etc. – and a type of saag, Julekha and Shahil have planted them all with love.

They along with two other men collect scrap from the roads. This week’s worth, which is stacked behind the kitchen garden and covered under sheets, will bring them good income. A few containers filled with water are also hidden under big covers. Julekha lifts another sheet to show a single gas stove and hides it quickly.

“How can they go to the shelter?” asks Rana. “All of this will be stolen. What will they eat?” he adds.

Rana himself has a rickshaw to take care of. As we settle at the fireplace again, Shahil jumps the ledge, pulls Rana’s rickshaw to the corner, locks it and throws the key to him. The small man is still smiling and warming his hands. The other man is retiring for the night. He stretches under his tree to sleep and rolls the blanket up to his chin. A handicapped chair is kept close to him. “A handicapped person lived here. He has now shifted to a colony. But he left his chair behind under our watch. He trusts us,” explains Rana.

Tired of his stepmother’s beatings, Rana ran away from home in Kolkata when he was in fifth standard and came to Delhi with his friends. He used to clean the public toilet on the pavement where he lives now. He used to earn Rs 5,500 a month. He now earns Rs 250 per day with this rickshaw which he bought for Rs 9,000.

Seven years ago he married a woman, who used to beg at the traffic signal and they rented a room for '1,500. “But she left me,” Rana’s eyes are fixed on the key with a dirty thread that he keeps rolling between his fingers. She took his son along for which he cannot forgive her.

With his eyes still facing the floor, Rana takes out his day’s earnings from his pocket. It’s a thin stack of light notes. Between the ten and five rupee notes, he has his son’s photograph. He has a beautiful smile, mischievous eyes and chubby cheeks. “I named him Farhaan, joining my wife’s and my name,” Rana smiles. His wife’s name is Fatima. She gave him the name Azad. “Is there a sabzi mandi near Azadpur?” Rana asks. Farhaan, or Azad, now lives in a children’s hostel there.

As we jump over the ledge, light shines from under a brick near a light pole. Rana’s phone is connected for charging to the wires hanging from the pole. He doesn’t have a sim card yet but if you come there on any night, you will find him under his tree. “If a person takes up any of the two jobs – of a rag picker or a rickshaw puller – he will not wander anywhere else,” Rana tells me. “It is difficult to settle at new locations with these jobs,” he explains.

We will find Julekha and Shahil also under their shed. She took a long time neatly folding their voter ID cards in her plastic pouch while Rana was talking. Doggy is visibly bored. He walks lazily to his spot under the tree, rolls and falls asleep.

As we walk back to the shelter, the fire burning at the footpath has turned cold. The couple has gone home. The man with the crutch at the bus stop has snuggled in his bed under the bright white light.

The change – and why it’s not enough

One can tell about a society by the way it looks at its poor; how respectfully it feeds them and how it defines dignity, says Dr Amod Kumar, head of department, community medicine at St. Stephen’s hospital.

Kumar, who has been working with the homeless since 2008, says that Delhi has come a long way in what it does for its homeless population. There were days when Delhi had only a few tents for them. “Tents catching fire was a frequent affair.” After much struggle, the Delhi government accepted that the homeless are the state’s responsibility. “We are a welfare state. It is the state’s responsibility to provide for the homeless persons,” Kumar stresses.

‘Mother NGO for Homeless’ was set up by Kumar in August 2009. It linked six field NGOs operating and managing the shelters with the government. The same year the state pledged '35,000 per shelter each month.

Meanwhile, the Delhi high court and the supreme court (SC) also got the state moving. The SC in 2010 ordered the shelters across the country to provide basic amenities like blankets, water and mobile toilets to the homeless. The high court also directed the state to issue antyodaya ration cards to all homeless people, treating them as the poorest of the poor.

In 2011, the state started setting up porta cabins or the tin shelters that we visited. “I just had 24 hours to decide the structure of a porta cabin. We received a call from the Delhi government and were told to bring the design in 24 hours, or we could forget about it,” recalls Kumar. He remembers the mad rush in his team. “No architect was willing to work on a short deadline. We had no option but to design it ourselves,” he smiles.

DUSIB, the department in charge of arranging for the homeless persons, now runs close to 200 shelters. These include 84 permanent brick and cement buildings, 111 porta cabins and 29 tents. Two shelters are also run by the Delhi Metro. Each shelter, which is given to NGOs through bidding, has toilets and water tanks.

To prepare for the harsh winters, the Delhi government had inspected the shelters in July; wherein 96 were found with poorly maintained toilets and lacking in other basic amenities. In August a government board reviewed the maintenance of these 96 shelters after which contracts of four agencies or NGOs were cancelled and fresh bids to run 66 shelters were invited.

“Many agencies did not have an idea how to deal with the homeless,” says Bipin Rai, a member of DUSIB, who headed the review committee. “A major problem found in the shelters was lack of sensitisation,” he adds. The committee recommended installation of hygienic toilets and bathrooms, and repair work at various shelters.

The streets of Delhi are full of Ayub, Mohammad Sayeed, Bismillah Khatum, Rana, Shahil, Julekha and many more homeless citizens who fuel the capital’s economy with their cheap labour, yet sleep on the roads. Many of them fear that their limited belongings will be lost. They cannot leave their rickshaws and carts unguarded. The small lockers that some of the shelters provide cannot store bulky material and thus serve no purpose.

Rai agrees, “Storage is a challenge. Though some of the shelters do provide storage facility but we need to make proper arrangements everywhere. Often people who deposit their belongings in the night forget to take them back the next morning. As they often work in different areas and do not sleep in the same shelter every night, they return as late as after two months to collect their belongings. Keeping a record of this and also vacating the lockers for the use of others becomes a problem,” he says.

Anwar Ul-Haq, national head of Hausla NGO’s urban homeless unit, says that if the caretakers and the NGOs can ensure people that their belongings will not be lost, many more homeless will sleep at the shelter.

Hygiene at the porta cabins remains an issue, says Kumar. In the last week of December, 8,000 to 9,000 homeless used the shelters and its blankets. At such a rate, the chances of transmission of communicable diseases among the users increase considerably. “People cough in the blankets. They also catch lice easily,” he says.

As per DUSIB’s draft agreement with the NGOs, the latter is responsible for getting the blankets, issued to it, dry-cleaned. According to the draft provisions, the government pays '15 per blanket, just once a year. This would explain the lack of hygiene. For washing of durries, '10 is to be given once every three months. “We had suggested that the blankets should be ironed every day to kill the germs as people who frequent these shelters use different blankets every day,” says Kumar.

In the wake of above practices carried out at night shelters, first-aid and treatment of diseases becomes all the more important. “Inside the shelter, the deaths are mainly due to diseases. Though there is provision for first-aid and doctors visit on a regular basis, if one is suffering from a major disease, it becomes difficult to provide immediate treatment. The government has the potential to do more,” says Pandey.

As per the SC guidelines, one shelter is required per one lakh population in all major cities. But NGOs feel that this rule need not be applied in areas where there is no homeless population. On the other hand, “more than one shelter is required at locations where homeless population is concentrated. Building shelters in posh colonies is of no use. Residents don’t allow the homeless to be there and the homeless too are hesitant to go and stay in those shelters,” says Abdul Shakeel, campaign coordinator, Housing and Land Rights Network, a non-profit working for the homeless. Also, for families, living in a shelter is an option they seldom choose. “The existing shelters do not cater to the needs of families. There is no privacy,” says Shakeel.

The Delhi government, meanwhile, has set up 47 additional tents in the city where concentration of homeless people is more. Of its total capacity of about 19,000 in all its shelters including temporary tents, the average occupancy remains only half. For instance, 420 people can be accommodated in the shelters in Jama Masjid while 350 in Nizamuddin. But the night we visited, the Jama Masjd shelter had 339 people and Nizamuddin only 251.

On December 4, the Delhi government started the rescue mission for the homeless with a phone application called ‘Rain Basera’. Anyone who notices a homeless can send photographs and other information of the location through the application. DUSIB then passes on that information to the 20 rescue teams across the city that work between 10 pm and 4 am every night. The rescue teams search for the homeless person and take him or her to the nearest shelter.

People can also call on DUSIB’s control room and provide information about homeless people. Inside the control room, three young men sit behind modest desks and with computers giving them live occupancy of the homeless shelters. As many as 168 calls to rescue the homeless had been made to the control room till the evening of December 23.

The purpose of these measures by the government is to ensure that no person sleeps out in the cold and is given relief immediately, but the rescue of homeless persons is not as simple as it sounds, says Ul-Haq. He along with his team members, recently stopped police officials who were forcefully transferring homeless people to rescue vans to be taken to the shelters. “They should have at least listened to the concerns of the homeless, and their reasons for not sleeping inside shelters. Using force is completely unacceptable,” he says.

“The homeless people are highly territorial. They live in areas with which their livelihood is associated,” Kumar explains why the ‘rescue’ operations are difficult. When he started work on the streets of the city, funds were always a challenge and donors never found the exercise of rescuing homeless cost-effective. “I started rescuing homeless persons in my car,” Kumar adds.

The definition and the numbers

But who are the homeless and who should be ‘rescued’? Though it sounds simple, the word ‘homeless’ is a grey area when freebies are announced.

“There are many definitions of a homeless – census has its own, civil society has its own and the Delhi government, too, has its own. DUSIB defines a homeless as anyone who does not have a roof over his head. If there are people living in slums, kuchcha houses or in some other resettlement, we do not consider them homeless,” says Rai.

Census defines ‘houseless’ as persons who are not living in buildings or in a structure with roof, but live in the open on roadside, pavements, in hume pipes, under flyovers and staircases or in the open in places of worship, mandap or railway platforms.

The supreme court commissioners office, meanwhile, has recommended expanding the definition of the homeless to include those who spend their nights at night shelters, transit homes, short stay homes, beggars’ homes and children’s homes. People living in temporary structures without full walls and roof, such as, under plastic sheets, tarpaulins should also be called as homeless, they say.

The ambiguity in the definition of the homeless has a direct impact on its numbers. Choose any number between 16,000 and 1.5 lakh, and that may be the figure of homeless living in Delhi. In 2008, Indo-Global Social Service Society (IGSSS), an NGO, conducted a head count of the homeless people in Delhi and found the number to be 88,410 with an estimation of 1.5 lakh people living on the streets.

In 2010, Mother NGO for Homeless surveyed 55,955 homeless in the city. The 2011 Census puts the numbers at 47,076 in the capital, while in 2014, a DUSIB head count found the most modest of all survey numbers – 16,000.

This winter, DUSIB has not recorded any deaths in the homeless shelters or of people dying of the cold in Delhi so far. The list of unclaimed or unidentified bodies as maintained by the Zonal Integrated Police Network or Zipnet also does not give an accurate figure of homeless dying due to the harsh winter. “All unclaimed bodies are not homeless deaths. Many among them may be people with homes who may be addicts and die on the roads,” explains Kumar. In order to get a more accurate figure, he says, the government should collect circumstantial evidence and conduct post-mortems of unclaimed bodies to find out the actual cause of death.

The DUSIB has no budget constraints for the homeless shelters, says a senior official, who did not wish to be quoted. The shelters, therefore, have to provide more than mere space to the homeless people to bring a change in their lives, Ul-Haq believes. “NGOs operating the shelters can help the homeless in accessing identity cards and give them vocational training so that they can take up jobs and start earning,” he says.

Also, instead of setting up temporary shelters, investing in low-cost housing or dormitories with subsidised food and space to keep belongings is one of the solutions, says Kumar. “Most of the homeless people are economically active, even if they are beggars. Most of them are socially responsible and send money back home to families. There is extreme poverty in the homeless population. It does not need too much money to cover it,” he adds.

sonal@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the January 1-15, 2015 issue)

At 10, we return to Urdu Park to check on the men’s shelter. The tent is finally ready, inside on the bare soil wooden beds are placed in a row. It is quite warm inside but the dust-laden still air is troublesome. Only three men are snuggled inside the blankets, though there is room for 30. Wasim, Noor and Shahrukh, all in their early 20s, work as helpers at weddings and also do odd jobs. They had been sleeping in the open until today – when they come to know about this shelter. “Outside, we have to pay as much as '40 for one blanket. Here it is free,” says a beaming Noor.

At 10, we return to Urdu Park to check on the men’s shelter. The tent is finally ready, inside on the bare soil wooden beds are placed in a row. It is quite warm inside but the dust-laden still air is troublesome. Only three men are snuggled inside the blankets, though there is room for 30. Wasim, Noor and Shahrukh, all in their early 20s, work as helpers at weddings and also do odd jobs. They had been sleeping in the open until today – when they come to know about this shelter. “Outside, we have to pay as much as '40 for one blanket. Here it is free,” says a beaming Noor.